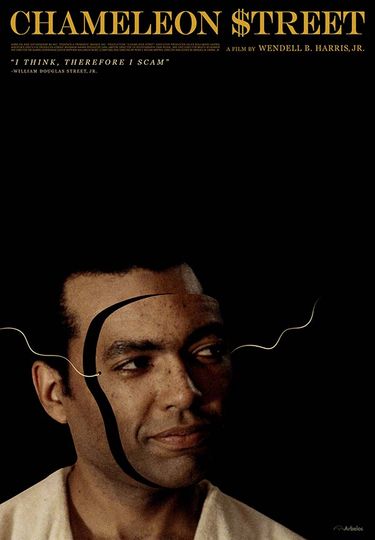

‘Chameleon Street’ Director Wendell B. Harris Jr. Discusses The New 4K Restoration Of The Film

The criminally underseen winner of the Grand Jury Prize at the 1990 Sundance Film Festival is getting a new restoration, supervised by Harris himself

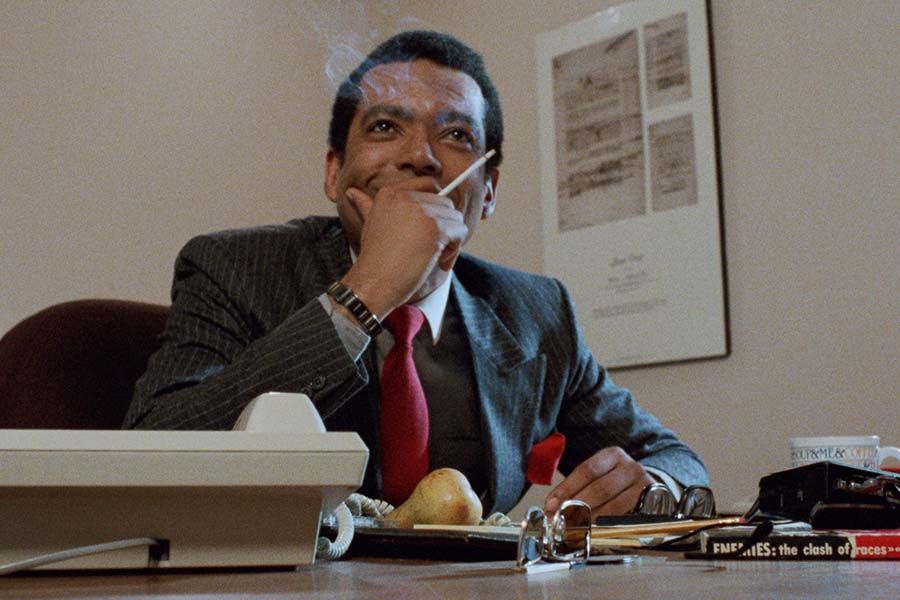

Actor-writer-director Wendell B. Harris Jr. as Douglas Street in 'Chameleon Street'

Wendell B. Harris Jr.’s subversive landmark film ‘Chameleon Street’ has been given a proper 4K restoration by Arbelos Films. Written, directed, and starring the Juilliard-trained Wendell B. Harris Jr, the film recounts the story of real-life con artist William Douglas Street, Jr., whose antics were often the fodder for salacious newspaper articles. The titular chameleon, Street impersonated everyone from professional reporters, lawyers, athletes, students, and even surgeons. Without a lick of professional medical training, he purportedly performed 36 successful hysterectomies! Although the film won the Grand Jury Prize after its premiere at the 1990 Sundance Film Festival, it struggled to find proper distribution and has long been considered a suppressed film. With its new restoration from the original camera negative under the supervision of Harris himself, the film is a must-see rediscovery.

Harris spoke to Moviefone about the film’s inspiration and legacy ahead of its run at BAM Film in Brooklyn.

Moviefone: What was so beguiling about William Douglas Street, Jr.’s story that you wanted to make a film out of it?

Wendell B. Harris Jr. : Well, I had been looking for years to find a vehicle for me that would provide a great acting role. I read the article in The Detroit News and I immediately knew that that was a great role. I immediately realized that Doug's experience was going to address issues that are the part and parcel of this country that rarely get really addressed. The Doug Street phenomenon involves looking under the carpet for the dirt that's been pushed and hidden there. Especially in regards to the interplay between Black people and white people, and the interplay between Black people and how they are permitted to live out their lives. The actual phenomenon of being Black in America is very connected to assigned roles. I don't mean biscuit rolls, I mean acting roles. You are born into this country, and you are immediately given a choice of two, three or four roles. That was so evident in Doug's story that the next day I began the effort of contacting Doug Street in order to get the rights for his story,

MF: Did you always plan to direct the film as well as act in it?

Harris: I was not going to be the director. Initially, the investors and my family and the Board of Directors of my company Prismatic Images, everybody essentially felt that for this first film we were producing we would get a director who had a track record. So we approached several different directors, including Marlon Brando, Melvin Van Peebles, Michael Apted, Stanley Kramer, in order to find an experienced director, and they all either turned it down. Brando didn't even respond, but they all turned it down, or they demanded too much money. So finally, I ended up directing it almost by default.

MF: Did your skills as an actor shape how you wrote the screenplay?

Harris: Doug Street’s entire modus operandi is based on acting, all of his achievements are connected to acting. So as the film was being written over that three-year period, and as I was constantly interviewing Doug, that was as critical to Doug's story as oxygen is to your breathing. I didn't have to sit back and try to work out. How does performance play a part? Everything he did was connected to performance. Had he not been able to act, to perform, he would not have achieved any of those goals.

MF: What was it like finding a crew and filming in Flint, Michigan at the time?

Harris: Well, the cinematographer was Daniel S. Noga. And the second unit director was Bruce Schermer. And Bruce Schermer, while he was working on ‘Chameleon Street’ was also the Director of Photography on Michael Moore's ‘Roger & Me’, which was shooting at the same time. We found 80% of our crew in Detroit, because Flint, Michigan did not have a lot of filmmaking crew members. That was crucial. When you're making an independent film, and it takes three years to raise the money, a lot of people tell you it will be a whole lot easier if you film the movie in 16mm. But I was determined from the moment I read that article, I was determined that this movie had to be made in 35mm. That meant getting a technical support group who knew what they were doing in terms of shooting a 35mm film. Initially we had agreed to hire a man who was a very experienced Director of Photography. He had shot ‘Beverly Hills Cop.’ We shot several tests with him, but eventually we decided to part company because he would not follow my directions. That becomes a big problem. So that opened the door for Dan Noga, and Bruce Schermer. They were a dream to work with, and unlike that first camera man, they actually collaborated with me.

MF: Early on in the film, you denote the passage of time by saying ‘Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman’ has gone off the air and ‘Mork and Mindy’ is now the top show. Could you talk a bit about the influence of 'Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman’ on ‘Chameleon Street’?

Harris: ‘Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman’ is still very important to me, and played a huge part in my life for several reasons. I wanted to pay tribute to ‘Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman’ in the script by mentioning it, although Doug was also entranced by ‘Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman.’ When I first went out to Hollywood, in 1977, I went out there in order to try and get a job writing on the ‘Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman’ staff. That did not work out. They turned me down. A few months later, the show was canceled, not because they turned me down, that's just what happened. I stayed out there for a year, going to audition after audition after audition, without an agent, which is extremely difficult.

Finally, I came back to Flint in 1978 and founded the studio, which is Prismatic Images. The whole point at that time was to put together an audio video film studio that would produce feature films. That was the goal. That was what I had not been able to even begin to achieve in Hollywood, with or without ‘Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman’. So I came back to Flint, founded the company and began the trek that led to ‘Chameleon Street’. We covered weddings and commercials and lotto commercials and all kinds of events. I worked on a radio series called 'Black Biography.' All of that led to finally producing ‘Chameleon Street.’ But your question about ‘Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman’ strikes me because nobody else has ever asked it before. ‘Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman’ was definitely an inspiration because of the ambiance that TV series promulgated.

MF: What do you think was so compelling about ‘Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman’?

Harris: ‘Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman’ lasted for two years and nothing like it had ever been done before. The most successful year was their first year. It was a very delicate mix and the second year they began to lose it. Like that expression from ‘Happy Days’ when Fonzie jumped the shark. That's the big danger for any TV series. It's amazing the way Peter Falk was able to always keep his focus of ‘Colombo'; airtight, laser sharp, no deviation. Whereas another show like ‘Monk,’ which began and was so amazing, but most shows a fall victim to as time progresses, the other characters surrounding the main characters begin to act like the main character. Everybody in ‘Monk,’ after like three or four years, they all got Monk-itis. They all know they all became like Monk, but Peter Falk never let that happen to Colombo. He always kept Colombo adulterated.

The second year of ‘Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman’, I think, began to fall prey to that syndrome. The first year it was all focused on Mary Hartman and everybody else was in her orbit, but they were not mimicking Mary Hartman's orbit. The second year, everybody began to get Mary Hartman-itus. They began to slightly lose their focus on Mary Hartman. I'll tell you an interesting thing about Mary Hartman, which was on at the time I was finishing up at Julliard. The one thing that was constantly on everybody's mind at Juilliard was acting. Acting was everything. Acting is all we talked about. And Mary ‘Hartman, Mary Hartman’, was such an inspiration to everybody in Juilliard, all these students, because Louise Lasser, she dared to on screen at the time, she dared to deconstruct the entire idea of a leading character in a sitcom or a TV series. She totally eviscerated the idea of a character going about whatever plot machinations they were going about. That was so inspiring to everybody at Julliard, and it certainly was inspiring to me. And it also plays a part when you look at Doug Street, because Doug is often deconstructing, moment by moment, the relationships that he's trying to push at.

MF: I love the retelling of The Scorpion and the Frog myth at the end of the film. Why did you decide to end it on that note?

Harris: There's a moment in ‘Mr. Arkadin,’ directed by Orson Welles, in which that story is used. It's a story that has been around for a very long time. I first came across it in ‘Mr. Arkadin’. After meeting Doug, interviewing him for three years, and writing the script, then rewriting and rewriting and rewriting, it became obvious as a coda for the film. The one thing that everybody who actually dealt with Doug ends up experiencing is the sting of betrayal. The same betrayal that the frog feels is the same betrayal that everybody who was interfacing with Doug feels.

MF: Why do you think this film was so challenging 30 years ago for Hollywood to sell?

Harris: I think that white audiences have a different experience than Black audiences. Over the last 30 years, as this saga of suppression has gone on and on and on, I have talked about it more and more and more. After the first 10 years, I began talking about how ‘Chameleon Street' is being suppressed, and then after 20 years I talked about it a lot more. After 30 years I'm screaming at the top of my voice, ‘Chameleon Street’ has been suppressed. But interestingly, whenever I have spoken with whites about that suppression. I never ran across anybody white who agreed with my assessment that ‘Chameleon Street’ has been literally suppressed. But I assure you, every Black person who sees the film and hears me say that it’s been suppressed, I've never had anybody Black say are you kidding? It's not suppressed. Every Black person who sees ‘Chameleon Street’ knows that it has been suppressed and understands why. So when you ask about reactions, I first think that the reaction of whites is different than the reaction of Blacks.

MF: Do you think audiences are more ready for a film like ‘Chameleon Street’ today?

Harris: I don't think that the audience has been the impediment to ‘Chameleon Street’. The audience was ready. In 1990, one of the greatest experiences of my life was seeing the reaction, that first reaction in 1990 and 1991. When people saw it for the first time, I got the most amazing reactions from white people and, and Blacks. Because, you know, they thought that ‘Chameleon Street’ was going to be like the harbinger of a whole new trend in movie making. That there was something about to happen that was fresh and vital and true, and not stereotypical. Not the standard fare that had been offered for like a century. Films are so powerful. I was so amazed because there was a kind of giddy happiness that I saw in people's reaction to the film initially, before it dropped off the face of the Earth. Before it was removed from global television. People thought, hey, things are about to get better. Things are about to be wonderful. There was this optimism to the reaction which I've never forgotten.

Arbelos Films’ new 4K restoration of ‘Chameleon Street’ had its world premiere at the 59th New York Film Festival and is now playing at BAM Film in Brooklyn. Upcoming screening dates can be found here.