Female Filmmakers in Focus: Director Tatiana Huezo Discusses Her Netflix Film ‘Prayers For The Stolen’

Welcome to Female Filmmakers in Focus, featuring recommendations for films directed by women to seek out each week. This week, Tatiana Huezo talks about her film ‘Prayers For The Stolen’ and the work of Finnish director Pirjo Honkasalo.

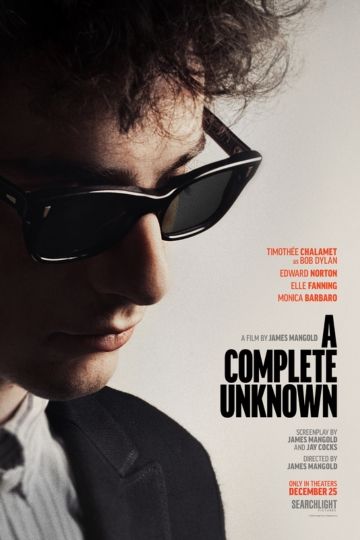

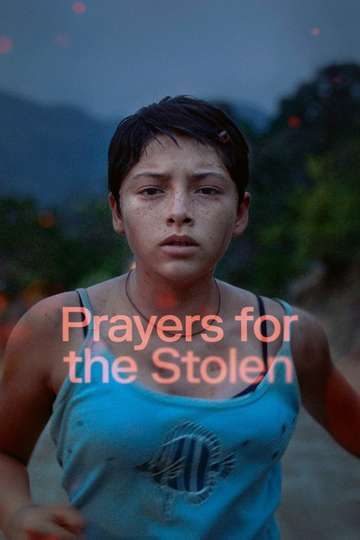

'Prayers for the Stolen,' directed by Tatiana Huezo

Born in El Salvador, Tatiana Huezo moved to Mexico at age four. Originally from the countryside, when her father moved the family to Mexico City, Huezo spent much of her youth at the film center watching the works of David Lynch, Wim Wenders, Andrei Tarkovsky, and Rainer Werner Fassbinder. She found her calling in the desire to provoke in others the same feeling these filmmakers made her feel. She attended the Centro de Capacitación Cinematográfica for undergraduate and received a master's degree in creative documentary at Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain. Her documentary work showcases empathy for the plight of everyday people in the wake of organized crime and war. Her feature film debut about the civil war in El Salvador, 2011’s ‘El lugar más pequeño,’ played in over fifty film festivals around the world. Her second feature-length documentary, 2016’s 'Tempestad,' is a look at how human trafficking affects two women in Mexico. That year, it won the Fénix Award for Best Documentary. Her latest film ‘Prayers For The Stolen’ competed in the Un Certain Regard section of the 2021 Cannes Film Festival, and is her first foray into narrative cinema. It is the Mexican entry for the Best International Feature Film at the 94th Academy Awards.

Based on the novel of the same name by Jennifer Clement, ‘Prayers For The Stolen’ tells the story of three girls and their mothers over the course of a few years as they work in the poppy fields of rural Mexico and attempt to keep their children out of the hands of human traffickers. Inspired by her own growing daughter, Huezo fuses magical realism with the grave emotional toll of the mounting violence in parts of Mexico. Featuring six young actresses playing the main girls at two distinct points in their lives, Huezo’s film honors the strength of these girls and their mothers, who despite all the adversity that surrounds them find fortitude to keep going.

‘Prayers For The Stolen’ is streaming now on Netflix.

Tatiana Huezo talked to Moviefone about her new movie.

Moviefone: How did you first come across Jennifer Clement’s novel?

Tatiana Huezo: Nicolás Celis and Jim Stark, the producers of the film, are the ones who first got the novel in my hands. They had already acquired the rights to the novel by Jennifer Clement. They said please read it and let us know what you think about it. It's a novel that really captured me and I read very quickly. I fell in love with the main character, whose name in the book is Lady D, but I called her Ana, and it's a child protagonist in the book. There was something that struck me from the novel, which was the fact that the mothers would dig these holes near the homes in order to protect their girls. Then I was also quite fascinated by the almost journalistic view of what it is like to grow poppies in the fields. I never really thought they were going to ask me to direct the film.

MF: What was the adaptation process like?

Huezo: They asked if I could write the script and it became a really interesting challenge for me. The only thing that I asked from the producers is that they allowed me to take it to a very personal place, and for me to be able to do a much more liberal adaptation because I already had other primary materials that I was working on alongside the novel. One of the most important things is the fact that I am a mother of a young child who was in the process of discovering the world. To watch her grow, to listen to her doubts, to watch the kind of games she plays, the magic that she involves herself in, was an inspiration for me. There are many pieces of dialogue in the film that actually belong to my daughter. Another of these primary materials that I was working with is that I've been working for a long time on these very difficult topics with women who are searching for their daughters. The script writing process was a very solitary process, and I discovered that I really liked it. I found it very fascinating to start to work on a script and to work on fiction. It took me about eight months to come up with a final script.

MF: What was sort of your biggest challenge shifting from documentaries to a narrative film?

Huezo: I think the biggest challenge is that fiction demands that you create everything. You have to create the rain, the wind. Every, every setting -- the poppy fields for example, every single one of the flowers is a fake flower that has been planted. All the spots on the walls, all the mold on the walls, are things that someone from the art department actually painted on the wall. That set where we have that final party with the cowboys was an abandoned soccer field. So everything comes from zero. You have to imagine everything. The color. The texture. Everything is not there to begin with. Whereas, in documentary, the spaces are there. The people in the circumstances are already there. I still sort of do manipulate a lot of color and even the clothes that the people are wearing in my documentaries. But even so, the context is already there for you. You don't have build it from scratch. That's the great difference.

MF: I found the haircuts on the girls and how the older girls have the same haircuts very effecting. Could talk a bit about the importance of hair on protecting these girls?

Huezo: That was a really important and very symbolic element for me in the film. The mothers need to extract things that belong to femininity in order to protect their daughters. It's a very difficult and painful moment in the film where they take something away from her that's very hers. It is a moment where she also loses some of her innocence. In the teenage years, this was very important for me that this happened with María, who's the girl who has a cleft palate, which is a makeup effect. That this was a whole new department for me - the art department. They constructed those cleft palates for both the girls. One of the things that I really wanted to come through is that none of the girls who grew up in this context are safe.

MF: Could you talk about your collaboration with cinematographer Dariela Ludlow?

Huezo: It was very important that she joined the project. She is a photographer and DP with a lot of experience. She's also a documentary filmmaker and also has the experience of shooting a lot of TV series and films that are quite ambitious in scope. I knew that she was someone who worked very quickly with light. It was also really important for me that the perspective from the camera was also a female perspective. I looked at a lot of the photographers across Mexico and I watched a lot of the films, because from the very beginning I knew this was going to be a handheld camera. There are very few operators that have the camera skill that I needed for the film. I do think Dariela is one of the best DPs that you can find in Mexico and has an exquisite eye for light. I had asked her to light the set 360 degrees so that the actors had freedom of movement across the set. She said no, you're really asking me to do something very difficult. But when I arrived on set, she had actually managed to put all the lights behind the doors or the windows, and instead used a lot of the lights that were already present there in the space. I think that Dariela also was a great influence in helping me to find what the color of the film was going to be. She had a very close and very deep relationship with the girls. She's also a mother, and I thought that was important for the camera's point of view

MF: When the film is over, how do you hope audiences feel?

Huezo: One thing that I want to get across to the audience with the film is what it means to have an irreversible thing happen in your life. What it means to lose someone that you really love. I would also hope that in the emotional memory and mental memory of the spectator that they don't think of these women as victims, but instead they see these women as strong women. That the girls are going to work like a seed in the life that surrounds them in the future. I do think the characters get this critical view that they acquire at the school about the world in which they live in, and that they question their reality. I would like to imagine that the spectator takes this film home and that the film and things from the film continue to resonate within them. Because I do think it's a film that asks the spectator to be a participant. The spectator has to imagine this horrible monster that we never actually see. And to feel it.

MF: Is there a female director whose work inspires you that you could recommend to readers?

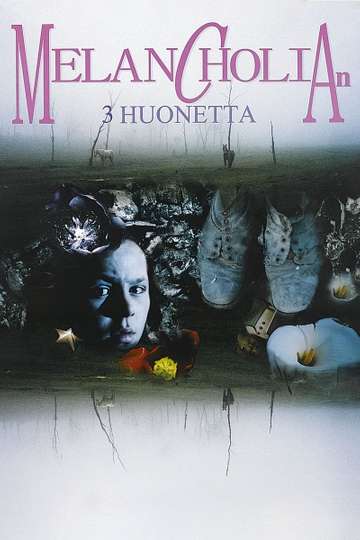

Huezo: There's a documentary filmmaker who's both a photographer and a director, who also produces her films. After doing documentaries for many years, she started doing fiction. She has an amazing point of view about the world, and also about childhood and teenagehood. Her films mostly take place during this time. She is a great creator of beautiful images. She's a Finnish woman. Her name is Pirjo Honkasalo. She has a movie called ‘The 3 Rooms of Melancholia’. It’s incredible.

The 3 Rooms of Melancholia - written and directed by Pirjo Honkasalo

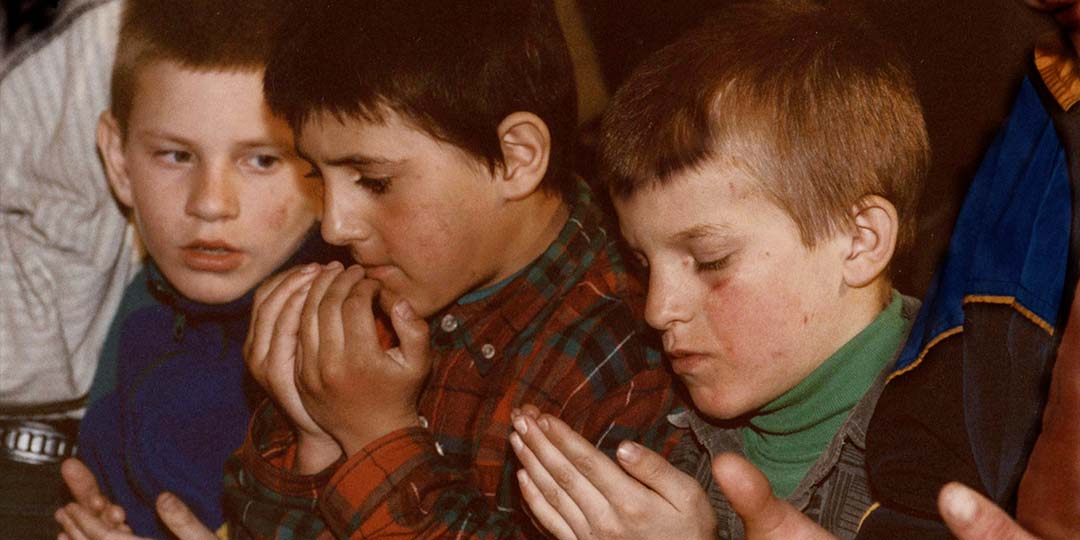

Boys pray at the Zihr ceremony

in Ingushetia in 'The 3 Rooms of Melancholia,' directed by Pirjo Honkasalo

Born in Helsinki in 1947, Pirjo Honkasalo graduated from film school at the age of 21, the same year she shot her first full-length film. After graduating, she studied and worked as an assistant at Temple University in Philadelphia. In 1980, she co-directed ‘Tulipää (Flame Top)’, a biopic of Finnish writer and journalist Algot Untola, which competed at the 1981 Cannes Film Festival. Best known for her documentary work in the 1990s, her Trilogy of the Sacred and the Satanic included the acclaimed films ‘Mysterion’, ‘Tanjuska and the 7 Devils,’ and ‘Atman’.

After completing the trilogy, she thought she was finished making documentaries, however Honkasalo later said she was drawn back to the format due to her interest in the poetic and the political. Her 2004 documentary ‘The 3 Rooms of Melancholia’ chronicles the aftermath of the Second Chechen War, specifically the psychological effects it had on the children of Chechnya and Russia. She ends her director’s statement for the film by stating that “grace is illogical and irrational - in other words, a profoundly gratuitous liberation from the compulsion to hate.”

The 3 Rooms of Melancholia

A searing examination of the unrelenting Chechen conflict, observed through the prisms of a Russian military boys academy, a war-torn town and a children's refugee... Read the Plot