Oscar Race 2018: Whose Voice Is Loudest?

Two big things happened in the Oscar race this past week. One was the announcement of the Directors Guild Award nominations, usually a strong predictor of the Academy's Best Director and Best Picture choices.

The other was that Academy voters turned in their nomination ballots, long before they can be influenced by the Screen Actors Guild Awards or several other precursor kudos. The SAG Awards will be handed out on Jan. 21, two days before the Oscar nominations are announced, but their impact on the race will be minimal to non-existent. From now until Jan. 23, everything that happens is just opinion-spinning that doesn't really matter.

Things are happening awfully fast this year, maybe faster than the process can handle. Last week, "Disaster Artist" star James Franco picked up two awards, at the Golden Globes and Critics Choice ceremonies, but if either of those awards had been handed out a few days later, if the voters had known of sexual harassment allegations against Franco, would he have won? Does he still have a chance at the Oscars, or were there still Academy members who had time to cross him off their ballots before Friday's voting deadline?

Academy members who want this year's awards to present Hollywood's best possible face to the world have a lot to think about already, without also having to worry about whether someone nominated next Tuesday will turn out to be a disgrace to the industry by Wednesday. Maybe they loved the artistry and historical sweep of "Dunkirk" or "The Post," but they wonder if either movie is relevant enough to a moment where giving voice to long-marginalized people seems a higher priority. (Certainly, this may be why "The Post," despite critical raves and the pedigree provided by Steven Spielberg, Meryl Streep, and Tom Hanks, has been largely shut out of major award nominations and wins so far.)

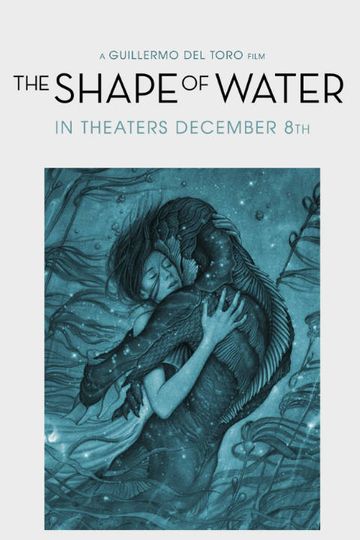

But then, which marginalized artists do you honor? The #OscarsSoWhite complaints of recent years seemed to get some redress last year with the Oscar victories of "Moonlight" (including Best Picture and Best Supporting Actor), but does that mean the Academy can safely ignore "Get Out" or "Mudbound"? On the other hand, the #MeToo and #TimesUp movement suggest that Academy will pay special attention to movies by and about women, but does that mean honoring "The Shape of Water," a movie with a female protagonist, but one who's literally voiceless? Or "Lady Bird," a film written and directed by a woman, with two vibrant female leads, but one that does little to address its characters' white and middle class privilege? Or "Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri," a movie with a strong female protagonist and a film that addresses sexual violence, but one that's written and directed by a man, and that's being criticized for supposed racial blind spots? What are voters to do regarding competing claims of marginalization?

Let's take a look at the DGA nominations, which went out to Guillermo del Toro ("Shape of Water"), Greta Gerwig ("Lady Bird"), Martin McDonagh ("Three Billboards"), Christopher Nolan ("Dunkirk"), and Jordan Peele ("Get Out"). It's a significant and even historic list. For one thing, it includes both Gerwig and Peele, who'd been left off some previous lists of directing nominees. For another, there's not one American white guy on the list, which may be a first. (Indeed, Gerwig and Peele are the only Americans among the five.) Perhaps most important, it's the first time that all the nominees also wrote their own screenplays.

Why does that matter? For one thing, it makes the Original Screenplay category a lot easier to predict. Second, the last four Best Picture winners also won Best Screenplay (either original or adapted).

Finally, it means all five filmmakers were telling highly personal stories. Critics may have singled out those of Gerwig (whose film has some directly autobiographical elements) and Peele (whose film is a metaphor about what it feels like to be black in America today). But the other directors' stories are no less personal, even if McDonagh has never been the mother of a slain child, or if Nolan was born decades after World War II, or if del Toro has never bonded with a creature who's part man, part fish. All five filmmakers are addressing themes and concerns that are deeply important to them and telling their stories in unique ways that reflect their own individual style as artists.

Of course, the same is arguably true for those eligible movies that did not get DGA nominations, including "The Post," "Mudbound," "I, Tonya," "Call Me by Your Name," "The Florida Project," "The Big Sick," "All the Money in the World," and yes, Franco's "The Disaster Artist."

At some point, it's worth remembering that these are movies, not group statements representing competing identity-politics teams, some long marginalized, some not. Each movie took as many as several years to make and was created in relative ignorance of its eventual release date or of which other movies then in production it might be competing with for the attention of viewers, critics, or awards voters. Many observers of last year's race tried to pit frontrunners "Moonlight" and "La La Land" against each other on the basis of their respective racial politics, but as "Moonlight" director Barry Jenkins noted at the time, neither he nor "La La Land" director Damien Chazelle conceived of their movies that way (they were just stories about the worlds they knew), and neither director had any inkling that their films would be awards rivals, much less pop culture proxies for factions of a divided America.

Similarly, the politics of this year's likely nominees matter, not because movies should be didactic or have messages that hit you over the head, but because everyone deserves to have a voice, and every aspiring filmmaker needs a role model. But what wins Oscars is a movie's overall narrative, and sometimes (maybe even most of the time), that narrative includes more than just what's on screen. It also includes the narrative of how the film reached the screen in the first place, and what drove the filmmaker who made it happen.

Ideally, that behind-the-camera narrative shouldn't matter to Academy voters, but it does, and it always has. The Oscars have never been about artistic merit alone, but also about politics, which is why handicapping the Oscars is a lot more interesting than just comparing each movie's Rotten Tomatoes score.

Of course, politics wouldn't be so much of an issue -- and competing claims from traditionally marginalized groups wouldn't be so hard to resolve -- if the Oscars, and the movie industry in general, had done a better job over the years of including everyone. Then it wouldn't be such a big deal to see Gerwig and Peele rubbing shoulders with McDonagh and Nolan. But we're not there yet, and it is still a big deal, and the Oscar race is still likely to come down not just to which movie is best, but also which movie makes Hollywood look the best at a time when what's going on behind the camera has become more important (often for all the wrong reasons) than what's going on in front of it.

The talented filmmakers among this year's likely nominees have proven themselves experts in telling their stories on screen. Once the nominations are out next week and the real campaigning begins, they'll have to prove themselves experts in telling their stories off-screen.