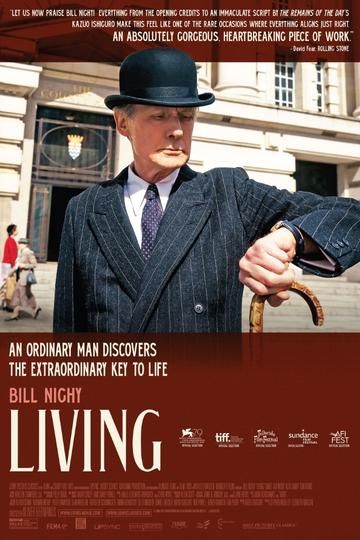

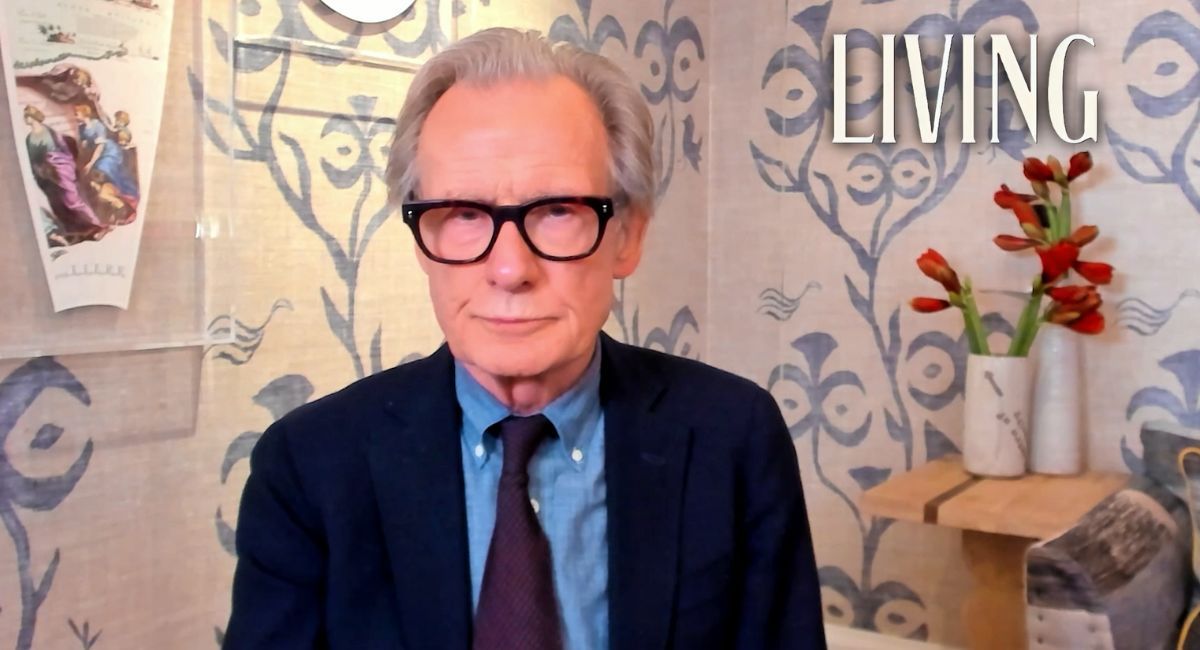

Bill Nighy Gives a Career-Best Performance in the Understated, Poignant ‘Living’

Oliver Hermanus directs and Kazuo Ishiguro writes this impressive remake of Akira Kurosawa’s ‘Ikiru’

Bill Nighy stars in director Oliver Hermanus' 'Living.'

Arriving in theaters on December 23rd, ‘Living’ sees Bill Nighy as a man choosing to try and live even in the face of death and is one of the most moving and poignant movies of the year.

Though his movies have been adapted many times––‘Seven Samurai’ alone is the basis for a wealth of other films––it’s still the brave filmmaker who chooses to tackle one of Akira Kurosawa’s classics.

In this case, the brave souls include writer Kazuo Ishiguro and director Oliver Hermanus, who bring a new version of Kurosawa’s 1952 drama ‘Ikiru’ to screens.

Instead of switching genres, the two have largely faithfully adapted the story (with some changes that shrink the running time to under two hours), moving the setting from 1950s Tokyo to 1950s London. It’s a smart choice, as the themes and emotions of post-war Britain were similar to those of Japan.

Bill Nighy stars in director Oliver Hermanus' 'Living.'

Bill Nighy––who according to Ishiguro was one of the reasons he thought the new film could work at all––plays Mr. Williams, a staid, buttoned-up civil servant who works in a department of the London City Council.

He’s so sunken into duty and free from emotion that co-workers joke about him being known as “Mr. Zombie.” It’s an apt description for a man who ostensibly appears to be alive, but only in the most basic fashion. Stiff upper lips have rarely been stiffer.

At work, he’s distant (though not always completely cold) with his colleagues and underlings and more concerned with shuffling papers than being concerned with anyone’s feelings. But then, he’s part of a generation of men raised to be proper and reserved, who have been through a global conflict forever changed.

Then, at home, the widower is still diffident when it comes to his son, Michael (Barney Fishwick), who, encouraged by wife Fiona (Patsy Ferran), is aiming to confront his father about selling the family home so they can get money to buy their own.

Williams’ world is detonated (albeit silently since he decides not to tell anyone at first) by diagnosis of terminal cancer. It does at least prompt him to act, leaving work for days on end and heading to a coastal town in search of something more in life. He meets and hangs out with disheveled, frequently drunken writer Mr. Sutherland (Tom Burke), who introduces him to the salacious delights of burlesque shows and crowded pubs, but despite opening up enough to start singing in one bar, Williams stills feels buttoned up, complaining that while he’s finally seeking out a life, he’s not good at it.

Aimee Lou Wood stars in director Oliver Hermanus' 'Living.'

He does at least find some solace in Miss Harris (Aimee Lou Wood), a young woman who had worked in his office before moving to a tea house in search of a better job. Her positive energy has a real effect on him, their chaste friendship becoming more of a motivator in his life, even if his son and daughter-in-law confront him about the potential scandal of Williams spending time with her––this is still 1950s London, don’t forget, where people of his standing are expected to be proper.

And at work, he also becomes more inspired, pushing to help a women’s group get a playground built on a patch of waste ground, seeing it as the most important legacy he can leave behind.

Opening with beautifully restored archive footage of the period before seamlessly segueing into the movie itself, ‘Living’ is a striking, moving achievement.

A lot of that is a credit to Nighy, who has excelled in light comedies and heavy dramas (and the occasional blockbuster, acting through CG prosthetics in some of the ‘Pirates of the Caribbean’ movies.)

Bill Nighy stars in director Oliver Hermanus' 'Living.'

Here, he’s the perfect stone-faced performer for Williams, able to imbue the man with an aloof sense of authority that melts into human realization as time marches on and the character learns of his fate. Nighy can say more with a twitch of his lip than some actors can with an entire monologue.

Which is not to say that Ishiguro’s script isn’t wonderful––it is, finding new layers to the story that even Kurosawa and his esteemed colleagues didn’t dig out.

Director Hermanus, meanwhile, stages it all with style and grace, an evocation of British life at the time that pops off the screen in different ways, whether it’s the forest of suits and bowler hats boarding a train at the start or the tents full of bawdy behavior that Williams experiences on his trip.

And Nighy is surrounded by some superb supporting cast members. Wood, a veteran of Netflix series ‘Sex Education’ is a real delight here, her sprightly yet demure Miss Harris a tonic for the viewer as much as she is for Williams. The likes of Alex Sharp, Adrian Rawlings and Oliver Chris shade in his co-workers even if they’re not the biggest part of the story.

Bill Nighy stars in director Oliver Hermanus' 'Living.'

And an awkward scene between Williams and his son is a masterpiece of frosty British reserve, emotions that are bubbling under the surface kept firmly in check.

If there is one downside to the film, it lies in the pacing towards the end (which also affects the original). Once the inevitable befalls Williams, those left behind are a little at sea, and the narrative is similarly impacted. A slightly overlong speech from a policeman reminiscing about having seen Williams sitting in the playground he helped make a reality feels uncomfortable and momentarily breaks the spell that the movie has so effectively cast.

Yet it’s a blip in an otherwise unimpeachable film that rewards patience and confirms that Nighy is one of the best actors working today. Like Williams himself, it might seem cold and mannered, but there’s a huge heart at work in ‘Living’.

‘Living’ receives 4.5 out of 5 stars.

Bill Nighy stars in director Oliver Hermanus' 'Living.'