Sam Mendes Explores Depression and the Magic of Cinema in His Latest

Olivia Colman anchors a melancholic but beautiful story set in 1980s England, which also features Micheal Ward, Colin Firth and Toby Jones.

Olivia Colman in 'Empire of Light.' Photo by Parisa Taghizadeh, Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures. © 2022 20th Century Studios All Rights Reserved.

Though they were both swirling around their writer/directors’ minds before the pandemic struck, it’s hard not to see Steven Spielberg’s ‘The Fabelmans’ and Sam Mendes’ ‘Empire of Light’ partly as reactions to cinemas being closed during the long months that everyone was locked down.

And while Spielberg took a semi-autobiographical approach to channel his love of watching (and making) movies, Mendes seems motivated more by the impact it can have on those who might need a boost. And about troubled people finding each other.

The setting for the ‘1917’ director’s latest is the chilly, windswept English coastal town of Margate, where stands one of the Empire chain of cinemas. There, a small staff screens the latest releases to local folk.

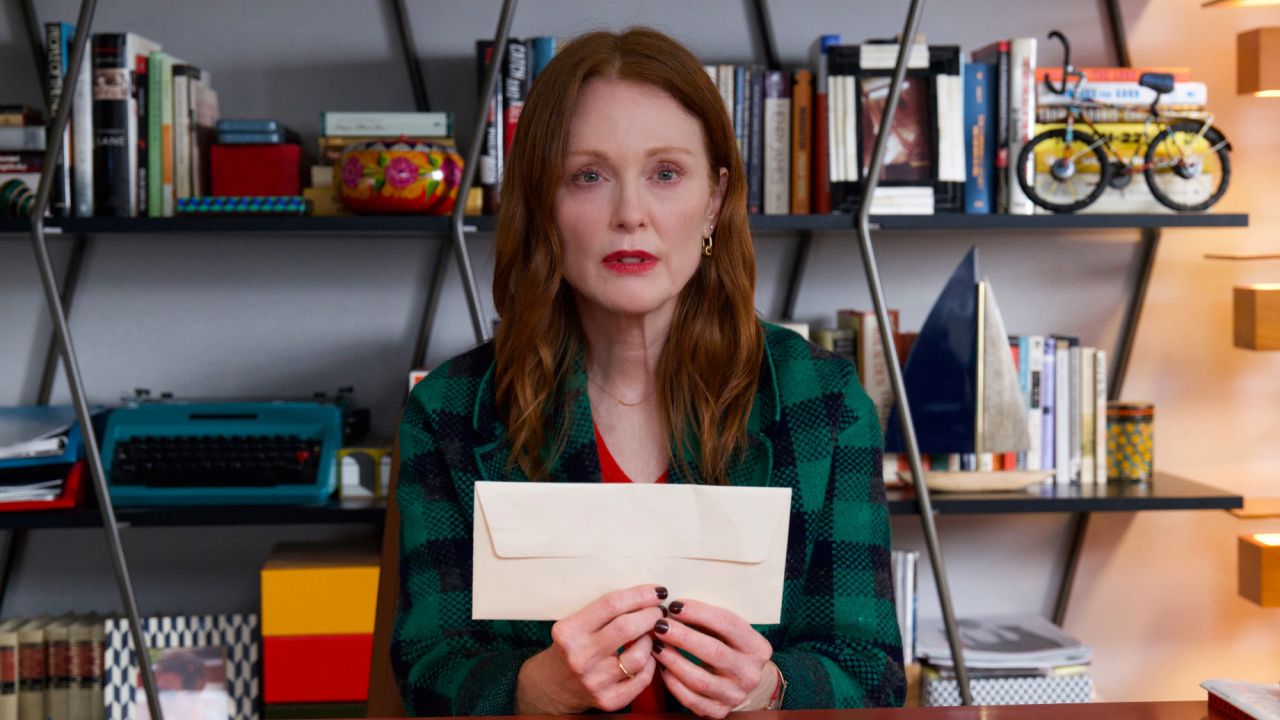

This old-school movie palace is falling into disrepair, entire sections locked off and some exposed to the elements, its glory days behind it. The same might be said for some of the staff, though in the case of the careworn manager Hilary (Olivia Colman), the question is whether she ever saw glory days to begin with.

The cast of "Empire of Light.' Photo by Parisa Taghizadeh, Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures. © 2022 20th Century Studios All Rights Reserved.

Back at work after a stay in a local mental health facility and facing little sympathy or understanding from her doctor, she’s just trying to hold it together while picking back up an ill-advised affair with the dull-but-authoritative Donald Ellis (Colin Firth, in particularly smug mode).

Around her are a rag-tag group of employees, including veteran projectionist Norman (Toby Jones), ambitious assistant manager Neil (Tom Brooke) and disaffected candy-slinger Janine. After a dismissal, their ranks are swelled by Stephen (Micheal Ward), an enthusiastic young Black worker with a love for music, who immediately attracts the attention of Janine and, on a deeper level, Hilary.

Soon, Hilary and Stephen are sharing snacks and sexual encounters in the disused upper echelons of the cinema, where a formerly fancy bar area is now home to roosting pigeons (Stephen rescues one in a slightly stretched simile for his relationship with Hilary).

Despite hailing from very different backgrounds and with starkly contrasting life experiences They’re drawn together by a shared love of music, cinema and figuring out their issues––her struggles with manic depression, he facing everyday racism in 1980s England, where the fascistic National Front is beginning to assert its power.

(L to R) Olivia Colman and Sam Mendes on set of the film 'Empire of the Light.' Photo by Parisa Taghizadeh, Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures. © 2022 20th Century Studios All Rights Reserved.

Mendes and legendary cinematographer Roger Deakins let their camera linger and rest, eschewing overly showy visuals in favor of beautifully lit moments that help the cast tell the story. And the watery sunlight of the coastal town also help paint the film in tonally appropriate grays, cut by fireworks and the neon lights of the cinema when it is gussied up for a “big” premiere.

It goes without saying that Colman is as excellent as ever. Brittle and withdrawn at first, though hiding that side with a forced cheery facade, she slowly unravels as the pressure of swirling emotions and years of trauma take their toll.

Yet she’s matched beat for beat by Ward, who offers a sensitive, charismatic portrayal of a young man still looking for his place in a world where he isn’t always welcome. Despite an early dalliance with Janine, Stephen lights up around Hillary, and Ward plays that to the hilt.

Firth sheds the charm that usually undercuts the stuffier characters he plays––while you can see why Hillary might be swayed by him, he’s basically a power-happy scumbag who bristles when he spots her while he’s out for dinner with his oblivious wife.

(L to R) Toby Jones and Olivia Colman in 'Empire of Light.' Photo by Parisa Taghizadeh, Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures. © 2022 20th Century Studios All Rights Reserved.

Around them, the rest of the employees are an appealing, if slightly archetypal ensemble: Janine as a punky rebel, Neil the lanky, agreeable type, Norman gruff but kindhearted. And then there are the customers, a quirky assortment of cinemagoers, some who need a little nudge in the direction of the rules (such as finishing your meal before stepping into the theater) and others who prove to be more hateful than the staff had suspected.

‘Empire of Light’ is largely a quiet drama punctuated by moments that pop, including Hillary’s stage-storming moment at the premiere to drop some truths and make a scene, and her ultimate dissolution.

Yet if Mendes true aim was to celebrate the power of cinema to lift you up, he falters slightly here. A lot of that heavy lifting is given over to Jones’ projectionist character, who has monologues explaining how his beloved machines work and the ability of what they project to lift hearts. It can be a little on the nose at times, and the actual act of watching movies is a sidenote until late in the film.

The director also seems unaware exactly where he wants to end his film, a couple of natural conclusions showing up and sliding by before the emotional punch of the real finale.

Tanya Moodie in 'Empire of Light.' Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures. © 2022 20th Century Studios All Rights Reserved.

A late act of racist violence, though keyed up earlier in the story, also feels vaguely out of place, the plot’s focus split for a subplot that has little fresh to say about race relations in the UK at the time and buttoned by an awkward scene between Hillary and Stephen’s mother Delia, played by Tanya Moodie. It does at least give us more of a glimpse into Stephen’s private life.

And none of its issues are enough to drag ‘Empire of Light’ into the murk. This is a thoughtful, reflective and often lovely film bolstered by its superb central performance and an evocative trip back to the 1980s (both their good and bad sides) likely to evoke nostalgic feelings even if you didn’t grow up in smalltown England.

With less of the self-conscious drawing on its director’s past than ‘The Fabelmans’, ‘Empire of Light’ offers its own dark charms and emotional fortitude.

‘Empire of Light’ receives 4 out of 5 stars.

(L to R) Micheal Ward and Olivia Colman in the film 'Empire of Light.' Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures. © 2022 20th Century Studios All Rights Reserved.