Female Filmmakers in Focus: ‘The Souvenir Part II” Director Joanna Hogg Talks About Her Latest Movie

Welcome to Female Filmmakers in Focus, featuring recommendations for films directed by women to seek out each week. This week, Joanna Hogg discusses her latest film ‘The Souvenir Part II’ and recommends Ulrike Ottinger’s film ‘Ticket of No Return.'

The Souvenir Part II - directed by Joanna Hogg

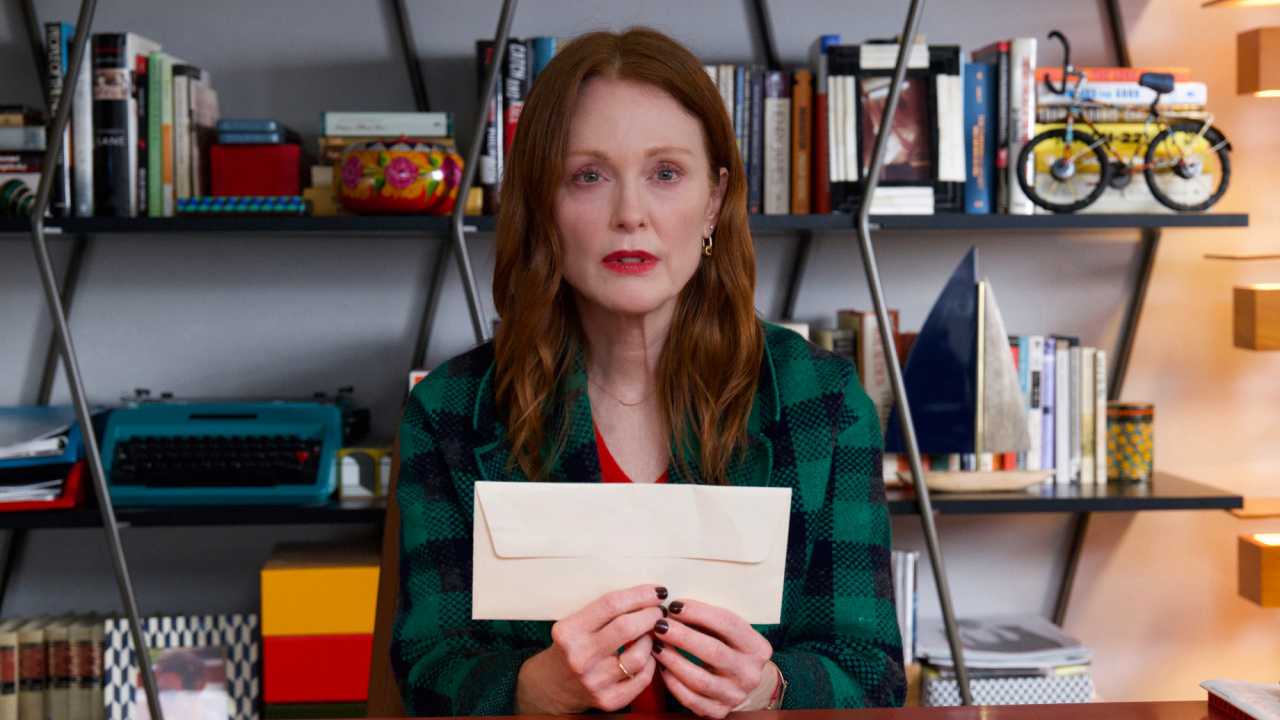

Honor Swinton Byrne and Tilda Swinton in 'The Souvenir Part II,' directed by Joanna Hogg

Born in London, England, filmmaker Joanna Hogg started her career making experimental short films shot on a super-8 camera she borrowed from mentor Derek Jarman - the two had hit it off after a chance meeting in a Soho café. One of her short films won her a spot to study filmmaking at the National Film and Television School, where her thesis film ‘Caprice’ starred a young Tilda Swinton. After graduating, she directed music videos for musicians like Alison Moyet, as well as many episodes of television. Her debut feature film ‘Unrelated’ starring Tom Hiddleston premiered at the London Film Festival in 2007, where it won the FIPRESCI International Critics Award. In 2009, Hogg was nominated for the London Film Critics' Circle 'Breakthrough Filmmaker' Award. Her next two features ‘Archipelago’ and ‘Exhibition’ also starred Hiddleston and received critical acclaim. Her semi-autobiographical fourth film ‘The Souvenir’ starring Tilda Swinton and her daughter Honor Swinton Byrne premiered at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival and was named the best film of the year by Sight & Sound magazine.

Set in the mid-80s, ‘The Souvenir’ recalls a passionate, doomed romance between film student Julie and a mysterious, older man named Anthony who supposedly works for the Foriegn Office. Following his death by heroin overdose, ‘The Souvenir Part II’ sees Julie back at film school as she works on her thesis film while attempting to process the impact of her intense relationship with Anthony. With the unflinching honesty of reflection, Hogg’s latest film finds inspiration in embracing growing pains, and opening ourselves up to truly feeling the weight of our emotional lives.

Joanna Hogg spoke to Moviefone about her new film.

Moviefone: Could you talk a bit about how your style has shifted through the years from your thesis film ‘Caprice’?

Joanna Hogg: I don’t know how much I'm aware of it in a way. But you mentioned ‘Caprice’, and looking at that again, definitely informed how I certainly made the film within the film in ‘The Souvenir Part II”. It reminded me of the invention and the ideas that I had at that time when I made it and before that, and how I wanted to kind of catch that feeling again, or catch some of those ideas again in order to get a sense of that time period.

MF: In ‘Caprice’ Tilda Swinton plays a young woman who gets sucked into the world of a glossy magazine. How did you first come up with that idea?

JH: I was really interested in how a young woman thinks of herself, or the doubt about how she looks and how she appears. And then the contradiction in me at that time of really being interested in fashion, and fashion magazines. But also about identity and recognizing that when I read a fashion magazine I would always end up feeling a bit sick at the end of it from the experience of being confronted with different images of how women looked or should look, and how you want to look like them. That journey of ending up feeling like I wish I hadn't read that magazine in the first place and looked at those photographs. I wanted to express that feeling of disgust and self disgust actually sort of journeying through a magazine meeting a magazine, but transposing that into her journey through the magazine.

MF: In the ‘Souvenir’ films Tilda Swinton plays the mother of Julie (played by her daughter Honor Swinton Byrne). Did you always plan to pair them as mother and daughter?

JH: I didn't. That just occurred because I ended up casting Honor, which I hadn't set out to do. That was by chance. In fact, when I first started thinking of the two parts I hadn't thought of Tilda as the mother until later on. Thinking about it now, it's kind of incredible that all those paths crossed in that way.

MF: What was the casting process for the role of Julie like?

JH: I was looking for someone who didn't feel that contemporary in a way. I would meet actors, meet filmmakers, I've interviewed people in the street, and there's obviously this preoccupation we have these days of FaceTime and all social networks. I wanted to find someone who was an earlier generation, almost innocent of all of that. It’s not like Honor doesn’t like social media herself, she does, but the was something about how she had grown up. She just reminded me a little bit of myself back at that time, and it wasn't even that I was looking for a version of myself exactly. It's hard to put into words, but I was very lucky to find her.

MF: The first film is sort of an idealized version of their romance, before its dark conclusion, and in the second film we step back and see those earlier events a little more clearly. How did you develop those two sides?

JH: Some of that happened on the journey of making the films. In the first part, Honor wasn't aware of the story that she was within, she didn't know where the story was going. So she wasn't in charge of that aspect. On the other hand, there was the experience of making Part I. Honor was, unbeknownst to me, observing me making Part I, and observing our own feelings about it as well. So with Part II, she knew the story because I told her where Part II was going to go, that Julie was going to be making a film. I'd seen that she was at times quite frustrated with Julia in Part I, and was really longing to break out of that character. It was always part of Julie’s journey anyway, but I thought it would be really interesting in Part II, if Honor got the chance to become a bit more herself in that part.

MF: ‘Part II’ reminded me a bit of that Joan Didion quote, “I have already lost touch with a couple of people I used to be.” Do you think the several decades' space between who you were when you went through the story that inspired the films and who you are as a filmmaker, if all of those reflections on the different selves that you've become helped you be able to see your earlier self more clearly?

JH: There's no question. If I'd made the film, when I first thought about it in 1988, it wouldn't have the layers and the experience that has gone into making it now. So I think, inevitably, yes.

MF: Tom Burke has such a strong presence in ‘Part II’ even though you don’t really see his character on screen. Was that a factor when you were casting ‘Part I’?

JH: I think you never know. I don't do screen tests or auditions or any of that kind of thing. I just developed a relationship with Tom. There was a lot of research, and we discussed the character a lot. He's an especially extraordinary actor. Someone I would really like to work with again. So I think it's a credit to his incredible performance in ‘Part I’, that his shadow is across ‘Part II’ the way that it is.

MF: How did you craft the scenes where Julie’s struggling so hard to communicate with her film crew, even though she knows exactly what she wants?

JH: They were really fun to shoot. Honor was really impressive, because she'd observed me directing ‘Part I’ and picked up so many thoughts and ideas of how we might describe how to shoot the scene, or where to put the camera or how to talk to the actors. It almost felt like we were shooting a documentary of a film shoot making those scenes. I decided on the scenes that we shot in ‘Part I’ that I wanted Julie to reenact in ‘Part II’. Once I had cast them and worked out the kind of basic mechanics, the cast just took off in their own way. They were making a film. It felt palpable, very real.

MF: I loved the way that you use the soundtrack to evoke feelings, and then you cut it in the middle of a song right before really catchy parts. When did you choose the songs for the film?

JH: I'd worked out some of those songs in advance. The decision of where to cut on a song, I think that's to do with rhythm. I think music can dominate a film so strongly, I sometimes don't want to get too carried away with the song because then I think one could lose the sense of where one is in the story.

MF: Could you talk about the significance of the title and the painting that inspired it?

JH: My relationship with that painting started many years before, when I was in a relationship on which ‘The Souvenir’ is loosely based. I was introduced to that painting. I think when I first started thinking about the story, and when I first started writing notes back in 1988 of the two parts it wasn't called ‘The Souvenir’ then. I hadn't thought about that. I can't remember exactly at what point I realized that was what I wanted to call it, but somehow that painting had made an impression on me. And it did seem very important for that person that I spend time with; I'm still unpacking it in a way I don't know entirely what meaning it had for him. But it felt significant.

MF: What do you hope people will feel after they’ve watched ‘The Souvenir Part II’?

JH: I don't know that I can prescribe that, but I do hope people can experience the two films together because I think that is an interesting way of seeing them. I don't think they're always going to be shown as a double bill, but I'm always interested if someone has seen the two films back to back, what they feel. I want to ask the question; I don't know the answer. I always want to know how someone has experienced the journey.

MF: Could you recommend another film directed by a woman that readers should seek out?

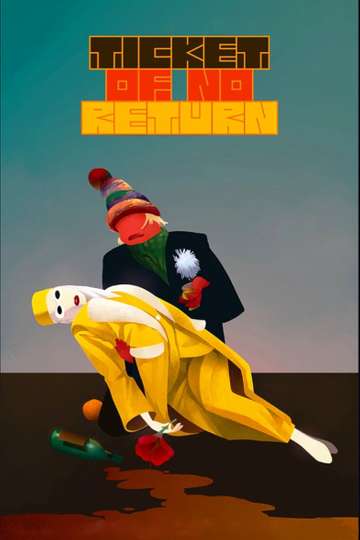

JH: There are so many. A film I’ve mentioned a few times over the years is by a German filmmaker named Ulrike Ottinger called ‘Ticket of No Return’, which is one of the films I saw very early on as a young student filmmaker that inspired me. I'm always interested in highlighting the lesser known or less appreciated filmmakers. I love Chantal Akerman. I think appreciation for her is now growing. Barbara Loden also springs to mind. I’m glad that people have revisited her work.

Ticket of No Return - directed by Ulrike Ottinger

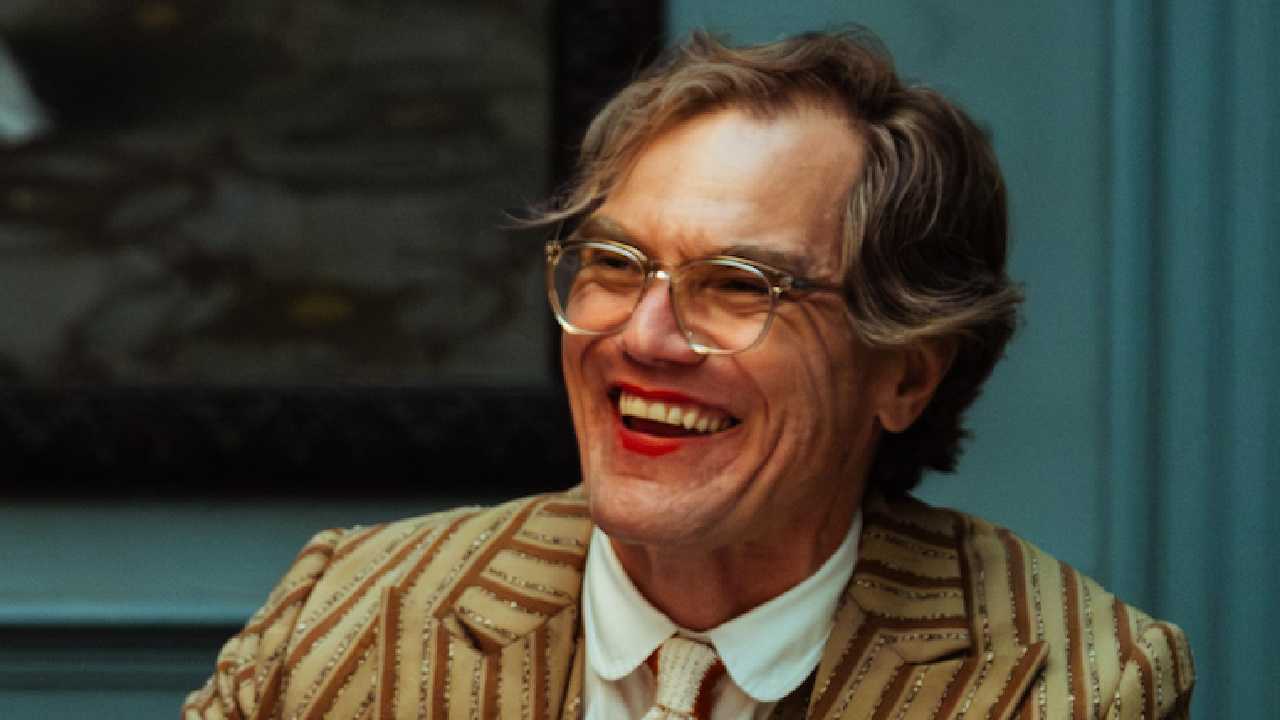

Tabea Blumenschein in 'Ticket of No Return' directed by Ulrike Ottinger

Born and raised in Konstanz, Germany, Ulrike Ottinger resided in Paris from 1962 until 1969, where she worked as an independent artist. Returning to her hometown, she co-founded the ‘filmclub visuell’ at University of Konstanz where international Independent Films, the New German Cinema (Neuer Deutscher Film) and historical films were shown. She shot her first film ‘Laocoon and Sons’ between 1971 and 1973, before moving to Berlin to pursue filmmaking full time. In 1979, she began work on what is known as her Berlin Trilogy, which consists of the films ‘Ticket of No Return’, ‘Freak Orlando’ (1981) and ‘Dorian Grey in the Yellow Press’. Openly lesbian, Ottinger has made over twenty films that push artistic and social boundaries. She was invited to join the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (who vote on the Oscars) in 2019.

The first film in her Berlin Trilogy, Ottinger’s vibrant ‘Ticket of No Return’ stars Tabea Blumenschein as an unnamed, yet incredibly chic, woman who travels to Berlin with plans only to drink and have a good time until she blacks out. A commentary on how women’s public actions are more policed than men’s, the woman’s every move is judged by a Greek chorus of commentators played by Magdalena Montezuma, Orpha Termin, and Monika von Cube. Keep your eyes peeled for German punk legend Nina Hagen amongst the film’s large ensemble cast of artists, writers, rockers, and drunks.