Female Filmmakers in Focus: Manjari & Vinati Makijany discuss their film 'Skater Girl' & recommend 'Mustang'

This week features an interview with ‘Skater Girl’ director-writer-producer Manjari Makijany and co-writer-producer Vinati Makijany, plus a recommendation to watch Deniz Gamze Ergüven’s ‘Mustang.’

Rachel Saanchita Gupta (center) in 'Skater Girl'

Sisters Manjari Makijany and Vinati Makijany have always had filmmaking in their blood. Their father Mac Mohan appeared in over 200 Bollywood films. In 2016, Manjari Makijany became only the 2nd Indian woman ever to participate in the AFI Conservatory's Directing Workshop for Women. She has also completed UCLA's Professional Screenwriters Program in 2015, the inaugural Universal Pictures Directors Intensive program and the inaugural Fox Filmmakers Lab in 2017. Co-written and co-produced with her sister Vinati Makijany, ‘Skater Girl’ is her first feature film. The film stars Rachel Sanchita Gupta as Prerna, a young girl living in a rural Indian village whose life is altered when she learns to skateboard. Fans of films like Haifaa al-Mansour’s ‘Wadjda’ will be moved by this delightful coming of age film’s heart and the way it captures the spirit of young women determined to forge their own path in life.

‘Skater Girl’ is available on Netflix now.

Skater Girl

Moviefone spoke to Manjari & Vanati Makijany about their new film.

Moviefone: What inspired you two to write this story?

Manjari Makijany: In 2017 I was sitting in LA and I had finished the AFI Directing Workshop for Women program, and I stumbled upon skateboarding in India and that blew me away because I had no idea that skateboarding was actually a thing in India. That fascinated me, so I did a deep dive, and discovered that there are a few skate communities in India. At the time, there were about 17 skate parks around the country. Also what skateboarding was doing in India, breaking through social norms, societal barriers and sort of age-old traditions, and really uplifting the communities where these skate parks were built.

MF: What was the co-writing process like?

MM: Vinati and I have been doing stuff together since we were in school. We would be putting on skits together, and on the drama team in college. We would host radio shows and competitions in our university. So we’ve always had a short hand at working together and that sort of organically translated into co-writing this project. We took a deep dive, journalistic search into how we could take this germ of an idea about skateboarding creating social impact in India and turn that into an entertaining while still being attentive to the subculture. We did a lot of back and forth. She was in India and I was in LA. She would write a scene and send it to me and I’d write a scene and send it to her. It was quite a process.

Vinati Makijany: Our co-writing process goes way back in time because I used to complete a lot of homework books for Manjari. That’s where it goes back to. I figured we’re good at writing together. We really enjoy telling stories together. As kids we used to love making up stories. This process of writing was super organic and so much fun. Of course there are deadlines. When you’re chasing a deadline you’ve set for yourself you have to be really honest with each other and that was really good that we could be brutally honest and say this is not working, let’s scrap it. Between Manjari being in LA and me being in India we could work 24 hours a day. When you find a really good scene it would make both of us happy. It was a very satisfying process.

MF: What do you think is so freeing about skateboarding and the subculture?

MM: This is a question we had for every skater we met in the US and in India. What is it that you like about skateboarding? Very few people could articulate what it was. It’s so visceral. That was a challenge to put into words. They would say, “I don’t know. . .we forget about our worries, you know? It’s just freeing. There are no rules. It’s like you’re flying.” Everybody was echoing the same thing, whether it was somebody in Venice Beach or whether it was somebody in Kovalam or Delhi or Bombay. How do you take this freedom and make it visceral on screen?

MF: Was there a specific kind of direction you gave the kids to get them to express that feeling?

MM: The younger the kids the more natural they are. They just take to it and enjoy it. We had a skate coach and trained all the kids for about five months because a lot of them you see in the film you see step on a board for the first time. The challenge was Rachel (Sanchita Gupta) who plays Prerna, her first time on the board she was really scared of skateboarding. So how do you take someone who is really scared of skateboarding and translate that and make it believable that they’re actually totally enjoying the freedom? It was a process, because not only is the character coming of age, but Rachel was coming of age herself through the process of finding freedom in skating. That was quite exciting.

MF: How did you find the kids for the cast?

VM: We were very clear about the faces that we wanted, the ensemble needed to feel real and not planted into this story. I went out and started workshopping with children in NGOs and government aided schools. Then we found casting director Sanjeev Maurya who was in Delhi. Together we were workshopping pan-India with 3,500-4,000 children. From that we found our actor kids who were brought to the skate park and trained in skateboarding. Then there were about 35-40 local children from that village who became a part of the movie as well.

MF: How did you find the main village location?

MM: We knew we wanted to set it in Rajasthan because it’s beautiful and it’s vibrant. The village we wanted to set it in needed three prerequisites: it had to have a lot of kids in and around the village because we were planning to leave the skate park as a community free public skate park. Then it had to have concrete roads in and outside the village so that the kids could skate if we gave them skateboards. Then the third thing was that it had to have that sort of rustic, rural vibe. Khempur checked all of these three boxes. This was the only village in Rajasthan that actually had makeshift skateboards. They never knew anything about skateboards before this, but they had these little bearing cars with a wooden flat and steel bearings that they would place with. They were really creative kids and we thought it was a sign that this was the place.

MF: Can you talk a bit about the film’s exploration of the caste system?

MM: We wanted to explore that without it being too on the nose, to find a very subtle way to do it. What we realized was that when we brought skateboards to Rajasthan, Vinati and I took my first skateboard around the place and had people step on it. That was quite eye-opening because it had such a novelty value. If you asked them to step on the board, the first time they just sort of beam this huge smile and they forget about things, these social norms they’d been following for a long time. Before people can figure out what are the rules around skateboarding, it’s just too late because they’ve already found their freedom.

VM: The caste system is still very prevalent in rural spaces, and sometimes we think, “oh stuff like that doesn’t happen.” But we experienced it first hand by people who don’t necessarily realize that it’s a bias. When we were constructing the skate park and I was staying there for a long time, people would just come in and ask me, “So, what is your caste?”

MM: They would just ask you straight up. “What’s your caste?” because they couldn’t figure out our background.

VM: So it had to come into the film in that very subtle fashion, but it also needed to be there. It was hard to not include such a reality.

MF: I love the older woman who helps them. When she says “Someday I’ll tell you my story” that was heartbreaking. Can you talk a bit about the importance of generations of women helping each other?

MM: We toyed a lot in the editing about if we should keep that line. We decided it should be there without us really knowing her story because that leaves it to the viewers imagination. I think that it was important to show that it’s a story about Prena, her skating and coming of age, but it’s also about all these different women who connect with each other and understand each other’s struggles. I think we are more similar than we think. It’s not about how different we are. Even from all the walks of life there is so much that we can connect to in each other.

MF: Can you name another film directed by a woman that readers should seek out?

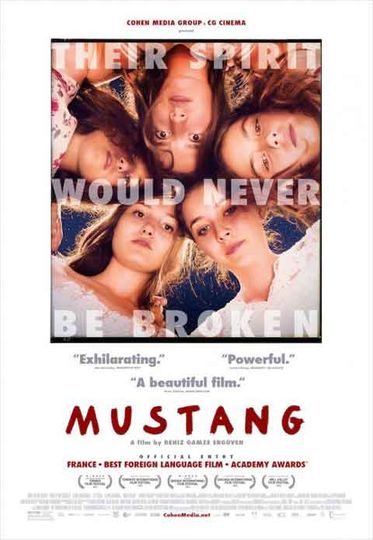

MM: I love ‘Mustang’ (directed by Deniz Gamze Ergüven). It was such a beautiful story and so well told and completely real. Go watch ‘Mustang.’ This is such a perfect example of not just on the screen, but also behind the scenes of a gang of women who just had a ball creating this film. You can see that bond when you watch the Q&As after you watch the film.

VM: ‘Mustang’ is also one of my favorite films. In fact, it was very inspiring for me. When I saw it I felt that this is the kind of film I would want to make.

Elit Iscan, Günes Sensoy, Doga Zeynep Doguslu, Tugba Sunguroglu, and Ilayda Akdogan in 'Mustang'

Premiering at the Directors' Fortnight section of the 2015 Cannes Film Festival, Deniz Gamze Ergüven’s ‘Mustang’ was nominated for Best Foreign Language Film at the 88th Academy Awards. The drama focuses on five sisters growing up in conservative rural Turkey. They find their lives more constricted after their favorite teacher moves to Istanbul and they must find strength in each other to rebel against their increasingly restrictive family. Bubbling with the same righteous anger as Sofia Coppola’s ‘The Virgin Suicides,’ Ergüven’s film is a lament for lost childhoods and an ode to female resilience.