Director Gore Verbinski Had a 'Cathartic' Experience Making 'A Cure for Wellness'

Gore Verbinski's "A Cure for Wellness" (out this weekend) is a bold, visionary horror epic that's unlike anything you've ever seen before. It's the kind of gonzo masterpiece that will be studied over and picked apart for years to come, and it's clear, from almost the opening frame, that it's a movie that only Verbinski could have made. And beyond it being a new Gore Verbinski movie, it's a wholly original film --one that has scope and scale and visual complexity. That's almost unheard of!

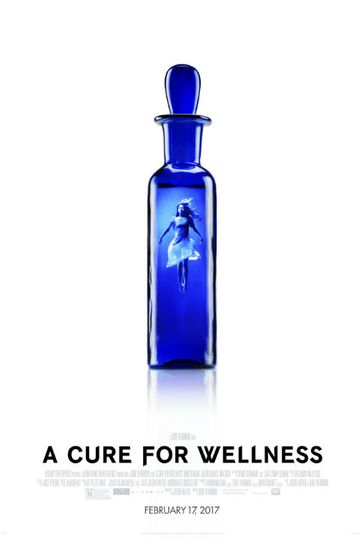

The film follows Lockhart (Dane DeHaan), a young Wall Street operative with questionable moral fiber, who accepts a job from his superiors to retrieve one of the founders of the company, who has been holed up in a mysterious German spa (the founder, Lockhart is told, is necessary for an important company merger). But this spa, as anyone who has seen a trailer for the movie (or looked at its ominous poster) can attest, isn't quite right ... Saying anymore would be downright criminal. But just know that this is a genuinely creepy movie that will stay with you long after you leave the theater.

I jumped on the phone with Verbinski to talk about the creative rejuvenation "A Cure for Wellness" represented (his last film was the outrageously underrated "The Lone Ranger"), where the idea for the film came from, what his "Bioshock" movie would have been like, and how excited he was to be scaring the hell out of people again.Moviefone: Where did this idea come from?

Gore Verbinski: Well, Justin Haythe, the writer, and I were walking and talking about different ideas. We're both fans of the novel by Thomas Mann, "The Magic Mountain." That was a jumping off point. We were also talking about genre pictures of the '70s and, in our favorite movies, there was always a sense of the inevitable -- like a hidden, unseen force. And what if that was a sickness? What if the narrative is this illness that the protagonist doesn't know about? It's the black spot on your X-ray. So it's the sense that he's being drawn to this place that maybe has been there, above the clouds, watching mankind from industrial revolution and the advent of personal computers to our obsession with cell phones, and offering a diagnosis. And it evolved from there.

What were your influences? It seems a lot like an old Vincent Price movie.

[Laughs] Well, certainly. I'm an [H.P.] Lovecraft fan. We are firmly rooted in the Gothic. But cautiously, because with those movies the curtain closes and you go, "Well, that was then." Because when movies really creep you out, they tap into some kind of contemporary fear. I think we're living in an increasingly irrational world. The movie is more prescient now than it was when we made it in 2015. But if you try and tap into some feeling, I like to think the curtain closes, and because we're diagnosing the modern man if you will, that it resonates when you think about it in a few days.

There are a lot of unanswered questions in this movie. Do you and Justin know the whole history of the facility and everything?

Sure, yeah. There's a whole map. But I think letting it remain slightly enigmatic has value as well. I think, when you watch it the second time, you'll see that it does add up. We really wanted to say, "OK, there's this guy and as he gets closer to this place his cell phone stops working and his watch stops." He's entering the world of dream logic. It's not a waking state. If we can get you nibbling at breadcrumbs rather leading you through the narrative, I think you prey upon your motivation to discover. If we just put things close together, it'd be easier to say, "Oh, that's related to that." But in a way, things can make sense in a dream.

It seemed like this movie was an effort to get back to basics, but then it winds up being two-and-a-half hours long and looks like it cost $200 million.

It's the same budget as "The Ring," it's just that we had a really great tax incentive in Germany. I deferred my fee completely and we don't have big movie stars, so there's very little above the line. It's all going on the screen. We are certainly not risk averse. It's all up there. Look, if you can stay the right size you can stay mobile. I went to Germany in the winter of 2015 looking for castles and found this one. So it was great for exteriors but the interiors wouldn't work. On the other side of Germany we found this abandoned hospital that had graffiti all over it and vines. So we tore the vines off and repainted it. So we're getting a lot of production value from traveling. If you can stay mobile, you can pick up a lot of production value from hitting the road.

Did you feel creatively reinvigorated by the experience?

[Laughs] Yeah, this was a reboot. It's cathartic. I do think that it's healthy to go to Germany and know nobody. It was a great chance to start over. You just grab a camera and make a movie.

Was there any pushback from the studio for an original movie of this size?

Well, the movie was produced by New Regency, which has a distribution deal at Fox. So they're kind of a mini-major. They were very hands-off. We had a bag that was a quarter full but we had autonomy. So we had to figure it out. That's the best way to operate if you want to try something different.I was on another set of another movie and your costume designer was saying that this was the weirdest movie she'd ever worked on, which I think you should wear as a badge of honor.

You know, it's good to be a little nuts. There's just something nice about ... Like the scariest part for me was on "Pirates 2" when the studio wasn't nervous anymore. They're smiling at you and going, "Just doing that thing you're doing, we love it." And you just go, "Holy sh*t." So trying to find the brink of uncertainty. That's where you want to be. You'll find it. Certainly "Cure" is way out there on the horizon.

Are you excited to scare people again?

Yes. It's a really great genre, in the sense that, in this case, you're following Dan's character as he reluctantly becomes a patient in this place. But really you're the patient -- you're in the darkened room and we're using sound and image and composition and performance to slow cook the audience. I think there's something beautiful in that.

It seems like the kind of timeless movie that people are going to be watching for a long time.

It needs to find its core, you know? That's harder and harder to do these days. We're out there, we're finding them, one by one. If it finds its champions, it'll be OK.

Can you talk about your composer, Benjamin Wallfisch? He seems to be part of your longtime collaborator Hans Zimmer's crew. The music in the movie is so great.

I'd never worked with him on all the movies I'd done with Hans. But I called Hans and said, "I know you're not going to be able to do this but I don't want to temp score this movie. I want somebody who is going to be with me for nine months." That's clearly going to take Hans out of the running. He recommended Ben and I really liked him. He's very classically boned. We never put a piece of music against the picture that wasn't original, which is really liberating. It's like crack. It's a self-fulfilling prophecy, especially if you're using a composer's other work against a movie. It's inevitable you get close to that temp score. So it was really important to say, "We're not going to go there."

Did you import any of the stuff you were working on for "Bioshock" into the thought process for this?

You're not the first person to ask me that, and I'm sure there's something subliminal. I think most people are reacting to the big isolation tank. I wanted to build something that really felt real. This is a strange meta-science that is happening here. This place is old but it's also operating in a kind of dream state. I needed the scale and I needed the pressure of all of this water and a place to put a camera and move around. So I went for it. And people said, "Oh, that looks really steampunk" or whatever. But the narrative is so different from "Bioshock." We're taking the tranquility and calm and purification of a wellness center and corrupting that, which is something else entirely.

How cool was your "Bioshock" movie going to be? Just level with me.

Well, we were going for it. We were going to push it all the way. There's no half-measures. It was a letdown.

Is there any chance of it being revived?

I don't know. When you're eight weeks before shooting, that's right in the transition; you're no longer the architect, you're the contractor. It's like, "Now I just need to make it." You enter triage mode. Most of the creative thought process takes place up until that moment and then it's the forces of gravity and physical reality and weather and all of that comes to bear and you move and you dance. Part of me is like, "I made it." That's the hardest part. We'd need a new financier willing to take the risk. But it would take a lot of work to get to that point, before you're ready to bite into it.

You have a few things on the docket.

You know that IMDb stuff is so out-of-date. That stuff is just ancient. There's a few things that have been on the backburner because "Cure" has been all encompassing. I'm not sure which one is going to go yet. I don't think any of them are on the Internet. That's so funny. You ask questions and I go, "Where are you getting this? Oh, I should go online."

Is there any inclination for you to return to animation?

Well that's one of the back-burner projects that is hopefully going to get going. You'll be the first to know. But I'm excited about doing animation again.

"A Cure for Wellness" is out this Friday.