'Creed II' Review: If Only All Sequels Were This Good

After six “Rocky” films, “Creed” was a remarkable triumph -- what seemed superfluous at best became essential.

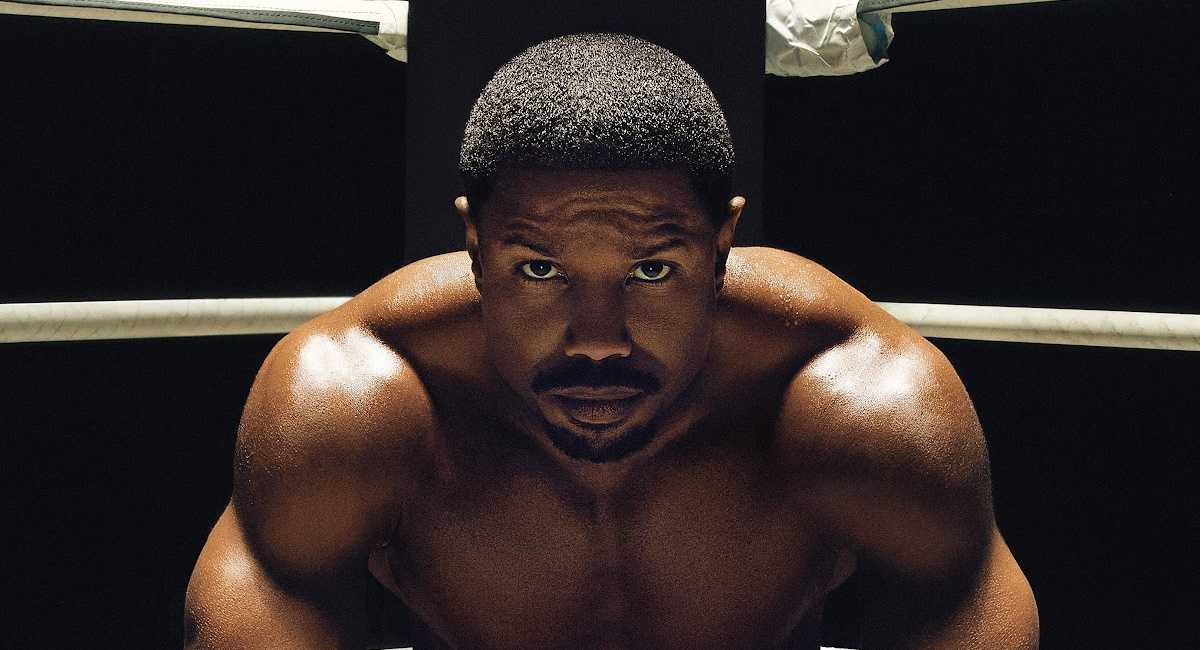

The first "Creed" movie is not just a great entertainment, but it is also a catharsis for one character and a vivid introduction for another. Consequently, “Creed II” only needed to be a well-deserved victory lap for Michael B. Jordan, who rocketed to stardom as Adonis “Donnie” Creed, not to mention Sylvester Stallone, whose signature series passed to more than capable shepherds. But like its predecessor, this kinda-sorta double sequel (both to its immediate predecessor and to “Rocky IV”) wrestles with powerful issues, deepens the first film’s characterizations, and resolves lingering details in the franchise’s timelines with humanity and grace. "Creed II" elevates the literal and metaphorical challenges of following up improbable success to something meaningful and eventually transcendent of the formulas that it relies upon.

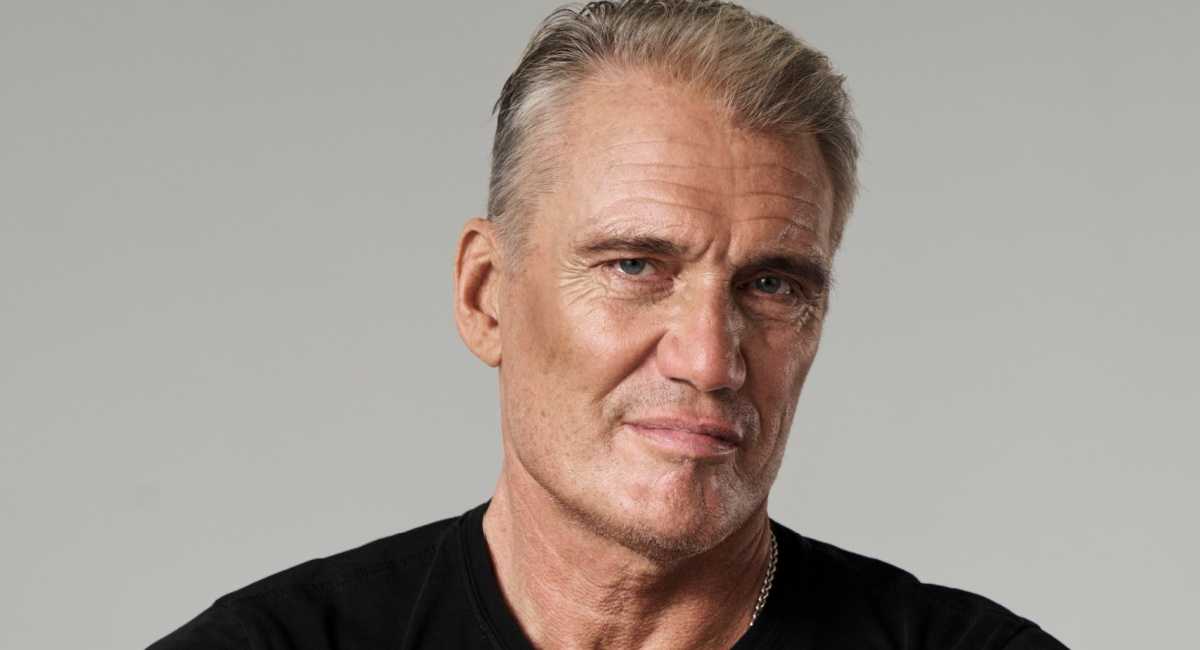

Following his bout with Ricky Conlan (Anthony Bellew) at the end of the first film, Donnie has spent his subsequent time in the ring proving that he can trade blows with the best in the boxing world, culminating in a decisive victory over Danny “Stuntman” Wheeler (Andre Ward) that makes him heavyweight champion of the world. But when ambitious promoter Buddy Marcelle (Russell Hornsby) approaches him with an offer to fight Viktor Drago (Florian Munteanu) -- son of Ivan Drago, the man who killed Apollo Creed 30 years ago -- Donnie jumps at the opportunity to avenge his father and burnish his own reputation in the ring.

Rocky (Stallone) discourages Donnie from facing an unproven fighter who’s been weaned on Ivan’s festering bitterness and anger, and who seems determined to exact as much pain as possible upon the protégé of the man who defeated his father. But when Donnie learns that Bianca (Tessa Thompson) is pregnant with their daughter, and should history repeat itself -- a defeat might deprive the newborn of knowing her father -- he is forced to contemplate not just whether or not he can win, but why it matters for him to fight in the first place.

Even as the film falls into the sometimes predictable rhythms of the series -- triumphant victories giving way to devastating defeats, and vice versa -- writers Sylvester Stallone and Juel Taylor showcase what seems like a very real feeling for competitors at the top of their game, and Donnie feels unfocused and perhaps appropriately decentralized in his own story. He is less a person than a character in a narrative that the world is determined to control -- a narrative that loves nothing more than perfect parallel lines between generations as one yields for the next to secure its own legacy. In the first half of Donnie’s journey, he seems to be doing what he thinks he’s supposed to, or is afraid not to -- a realistic and understandable course of action for a kid who, by the end of the first film, had only begun to discover himself, much less his febrile talents.

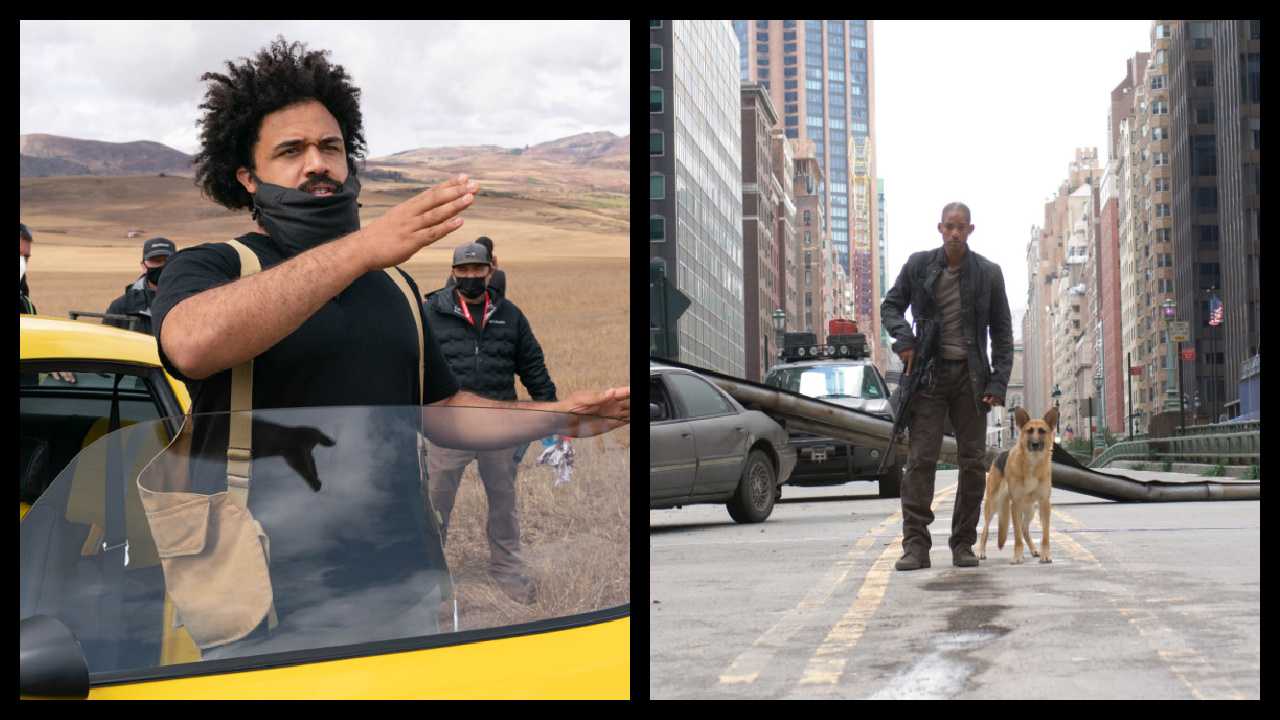

But abject losses have a way of forcing reflection upon people who pursue excellence, and director Steven Caple Jr. harnesses these necessary, almost predetermined story beats and turns them into moments of searing introspection -- and, eventually, powerful self-actualization. Jordan, proving again he has more than enough charisma and talent to be both a movie star and bona fide actor, returns to a character facing questions that undoubtedly hit close to home as he plots his next career move: Once you’ve earned success, how much is enough? And more vitally, what drives that pursuit? The young actor’s physical commitment to the role is readily visible, but it’s the overall sharpness of his performance, including moments of heartbreaking vulnerability, that elevate his journey from the son of Apollo Creed to his own man.

Meanwhile, the movie gives all of its characters much to do, and feeds off of their interactions in an uncommonly generous way. Tessa Thompson exudes self-assurance and restless creativity as Bianca, Donnie’s ride-or-die partner and sounding board. Bianca is skeptical in the most empathetic ways of Donnie’s pursuits and ambitions, even as she refuses to sideline her own.

As Mary Anne, Apollo’s widow, Phylicia Rashad continues to feed her adoptive son unvarnished truth and unconditional love, often dispensing one when he thinks he needs the other. And even if Rocky has largely accomplished all that the character ever needs to on screen, Stallone undercuts his shaggy authority as Donnie’s pride and fear becomes an uncomfortable mirror for the failures Rocky has left unresolved for too long. He shows that armchair philosophers can still learn as well as they teach.

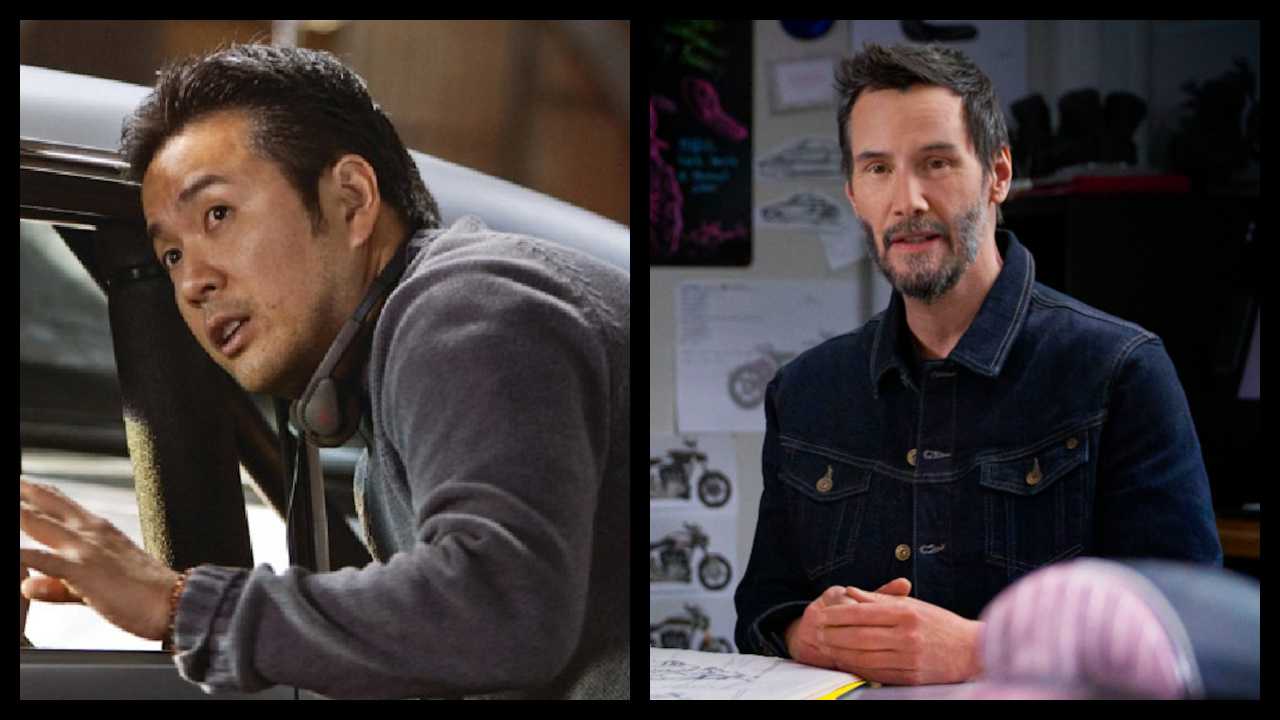

If the film falls short of its predecessor, it’s because the dramatic scenes are so good, and the journeys taken outside of the ring are so vivid, that the fights feel almost like an afterthought, or a concession to the demands of the series. Caple’s technique doesn’t quite feel as effortless or elegant as Ryan Coogler’s did on “Creed,” which may account both for the sequel’s over-modulated sound design -- every punch lands with an ear-shattering thud -- and its overuse of ringside commentators. (When the storytelling is otherwise this skillful, it feels unnecessary to have the stakes of the fight, including its “Shakespearean overtones,” repeatedly verbalized.)

But ultimately, Caple proves more than a worthy successor to Coogler (who returns as executive producer) in that he elevates and reshapes what could have been formulaic parallel story and character lines -- fathers and sons, mothers and children, legacies secured and destroyed, and purposes questioned and found -- into one converging, thrilling, deeply affecting narrative.

Because “Creed II” works wonderfully as a follow-up to the first “Creed” and the fourth “Rocky,” but the similarities to those earlier films are quite frankly the least of its charms. And like Adonis, what proves most remarkable is how successfully what could easily be dismissed as a lesser copy or pale imitation combats a suffocating legacy to prove it can, and should, stand on its own.