'Boy Erased' Review: Joel Edgerton Delivers Some of the Best Performances You'll See This Year

“Quietly exasperating” is the only note I took during “Boy Erased,” but it encapsulates much about what makes Joel Edgerton’s latest film such a unique and unexpected emotional journey.

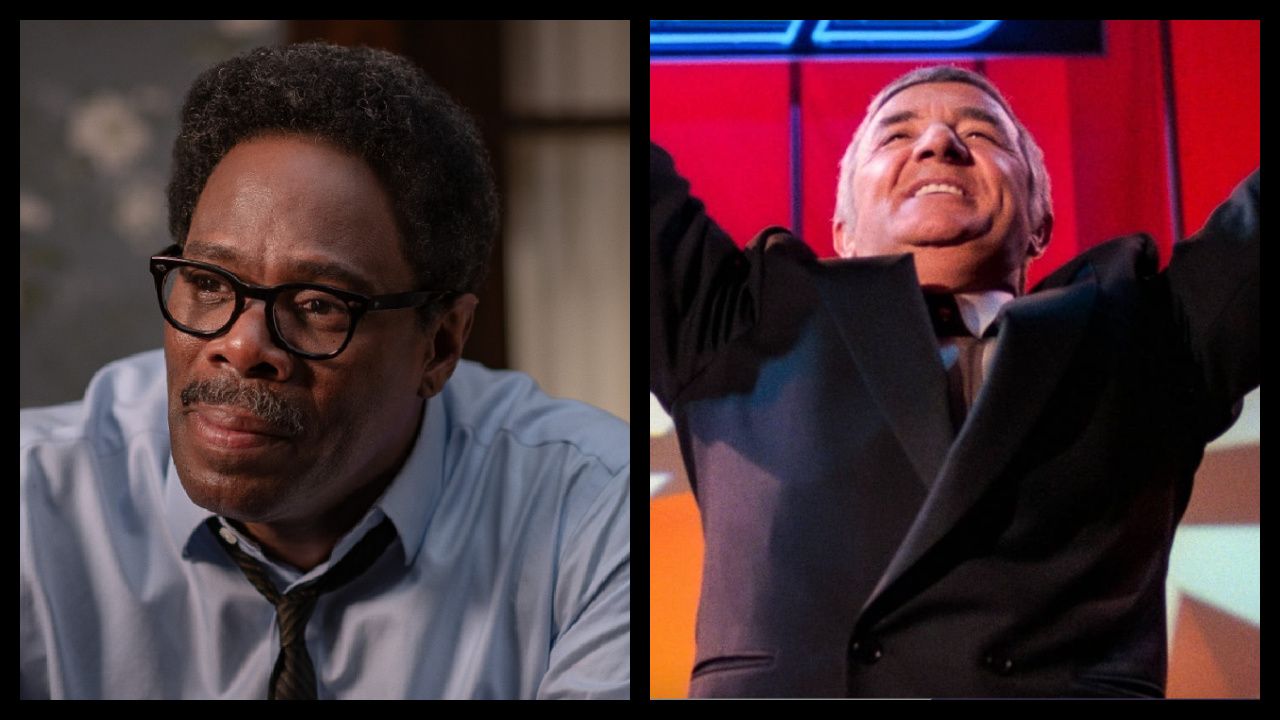

Extraordinary, nuanced performances from Nicole Kidman, Russell Crowe, Edgerton, and especially Lucas Hedges elevates this potential issue-movie melodrama to something much more broadly relevant, humanistic, and -- most of all -- hopeful. It chronicles the good intentions and terrible impact of gay conversion therapy as filtered through the experiences of one young man coming to terms with his sexuality.

Hedges plays Jared Eamons, the son of Baptist pastor Marshall, who agrees to go to gay conversion therapy after an incident at college outs him to his parents and the elders at his father’s church. His mother, Nancy (Kidman), is eager to see her son get the help that she and Marshall believe he needs, but is quickly skeptical of the program’s bona fides -- especially after Jared is asked by head therapist Victor Sykes (Edgerton) to catalogue their family’s individual transgressions. He's also asked to keep his requests for such information secret from family or friends.

As time passes and Jared begins to see its effect on his fellow participants, he becomes doubtful of the efficacy of the program, worrying that it is only clarifying and reinforcing the feelings that it is intended to eliminate. But as Jared becomes increasingly certain that his same-sex attractions cannot be drummed out by abusive harangues from Sykes and his staff, he simultaneously worries about the effect that coming to accept himself and his sexuality will have on his relationships with Nancy and especially Marshall, who struggle with the religious doctrine that continues to keep them at arm’s length.

What may come as the biggest surprise in Edgerton’s adaptation of Garrard Conley’s 2016 memoir of the same name is how understated so much of it is. Those expecting a depiction of conversion therapy as a brutal physical gauntlet for participants, or even one where they’re subjected to unrelenting verbal abuse, will discover that the process is considerably more nuanced, if no less deeply hurtful. Primarily, that’s because Edgerton -- pulling triple duties as actor, screenwriter, and director -- recognizes that many of the individuals who pilot such programs do have good intentions; they're eager to help young, confused people work through feelings that run counter to God’s teachings. But the program also requires few histrionics to underscore how disruptive -- and indeed, devastating -- it can be to a person trying to accept themselves for who they are, much less one in Jared’s case where the exposure of his “sin” was unwitting, and unwanted.

Hedges does an exceptional job navigating this fine line between dutiful son and self-actualized young adult. Jared loves his parents, and he attends the program as much because of his internal fealty to his own faith and upbringing as his sense of loyalty or obedience to Marshall and Nancy. It makes the central quandary of his attendance less about when he will finally recognize how destructive the program is, and more when he will finally accept himself for who he is and throw off the expectations and judgments of the adults who purport to control his emotional growth.

At the same time, the film doesn’t hold back on depicting the harm done by such programs, and showcases how their strict sense of privacy insulates them from too much scrutiny by the families of participants, but ultimately reinforces a cycle of secrecy and denial that seems destined to be implosive for young people fighting their own natural, healthy urges.

Crowe delivers a beautifully understated performance as Marshall, a father who loves deeply but cannot countenance his son’s sin -- meaning, he cannot understand it, and cannot confront it in even the most minuscule of ways. Kidman, meanwhile, provides a wonderfully transformative turn as Jared’s mother, a Southern woman who respects the authority of her husband until it is too late, and then can’t go back again -- especially if it comes at the cost of her son’s well-being. Their journeys run parallel to Jared’s, but the film sensitively portrays their own moments of discovery and enlightenment, just as it allows him -- when he is ready -- to express his own identity, not in a moment of anger or resentment, but confidence and clarity that, as parents he loves and wants in his life, they had better respect.

Maybe it seems unusual to suggest that a movie about such dire subject matter could be hopeful, but Edgerton accomplishes that feat with intelligence and tenderness. (The punctuation of end title cards revealing, in some cases, the hypocritical fates of conversion therapists offers enough of a rejoinder to conversion programs that a more theatrical comeuppance isn’t necessary.) Ultimately, “Boy Erased” is not just the story of a young man whose life comes into focus at the exact moment that his identity threatens to be eliminated, but a cautionary (if optimistic) tale about families -- communities -- that rely on rhetoric rather than love, and intentions they believe are good instead of the actions they know are right.