‘Gemini Man’ Really Is Unlike Anything You’ve Ever Seen Before

A lot of movies, especially if they’re saddled with some advanced technological breakthrough, claim to be “unlike anything you’ve ever seen.” But, more often than not, they are like something you’ve seen before, although slightly modified or embellished. After seeing roughly 20 minutes of Ang Lee’s upcoming “Gemini Man,” it’s safe to say that it is genuinely unlike anything you’ve ever seen before. Not only is this a movie where Will Smith is hunted by a younger version of himself, but it is captured and projected in 120 frames per second. Most movies are shot in 24 frames per second. So, yeah, we’re in uncharted territory here.

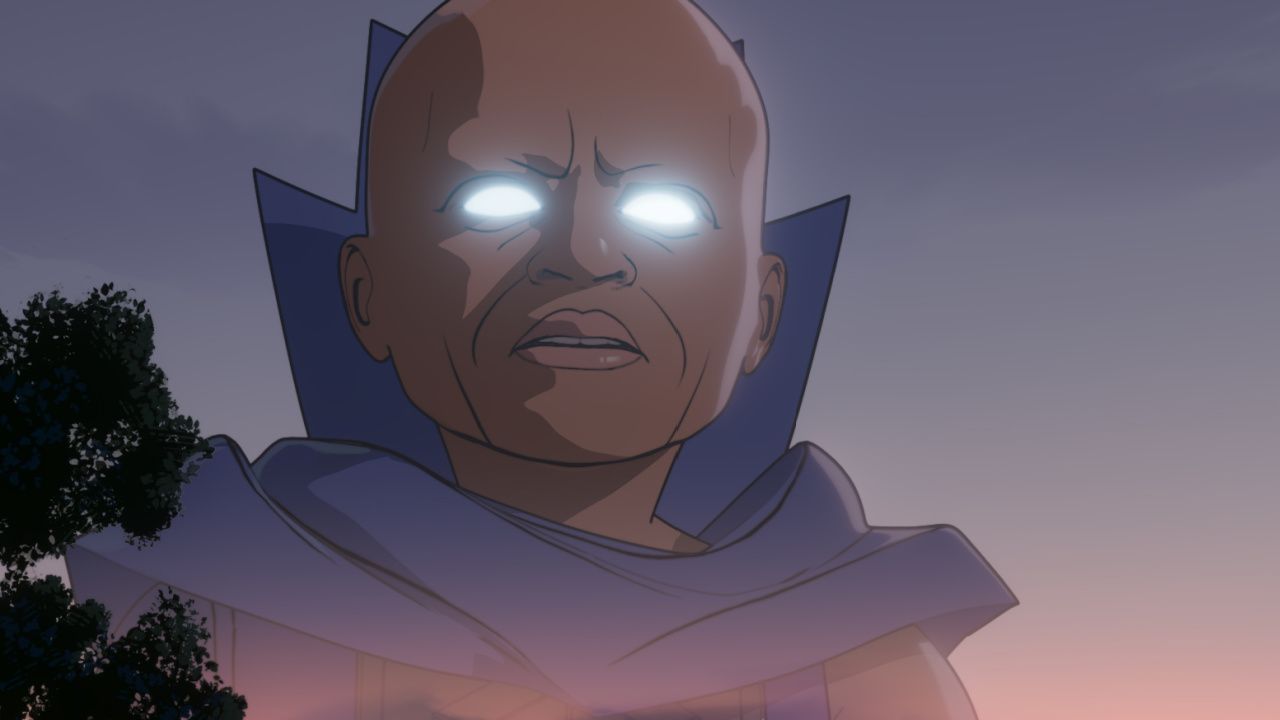

The footage we were shown consisted of three scenes. In the first scene, Will Smith is being targeted by a younger version of himself (referred to by Lee before the footage ran as “Junior”) and it really is astounding just how much this digital creation looks like a circa-“Bad Boys” Smith. It’s uncanny. (After the footage, Smith joked that since there’s now this exact digital double of himself, that he can take off several movies and let the clone do them.)

And the advanced frame rate and next-level 3D gives things an even more hyper-real feeling. Explosions don’t look like movie explosions; they look sparkier and more authentic. The story is obviously very stylized but these images have a realistic crispness that has never been put on screen before this film. (Keep in mind that Lee played around with the rapid frame rate and 3D for “Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk,” a movie virtually no one saw.)

Speaking about the technology after the footage, Lee said that “3D Is a different language,” and that he wasn’t trying to “just imitate film.” The rapid frame rate and 3D required a rethink of almost every aspect of the movie, since the whole production was being pushed in this new direction. “Lighting had to be more real,” Lee said. “This is a new aesthetic for digital cinema.” And he’s right, on all counts. This is not like the digital cinema we know – it’s not approximating the look of 35 mm (or 70 mm) film and it’s not looking intentionally crummy, like any number of found footage films. This is something else completely.

The second scene we were shown involved Will Smith’s character fighting Junior in an underground boneyard, a kind of catacombs setting. This is when the next-generational visual effects come into play, as Smith is literally punching and throwing his clone around a room. The fight was visceral and intense, made even more so by the fact that, at 120 frames per second, there is no motion blur. So you see every second of the fist landing into somebody’s face. And, again, the lighting was nearly non-existent in this scene, with the action illuminated by some strategically placed lights and that’s it. It really made you feel claustrophobic and in-the-moment, which is part of Lee’s whole design. He doesn’t want you observing; he wants you experiencing. For years Hollywood has been chasing that sweet spot between virtual reality and cinema and Lee and his team of collaborators might have actually uncovered it.

This sequence also has some very tender and funny moments, particularly when Smith is addressing Junior (you can see some of that in the terrific new trailer). What’s shocking is how well these smaller moments play (and they’re just as impressive as anything else).

Afterwards, at a visual effects presentation that I understood very little of, the effects supervisors talked about how, at a certain point in the catacombs fight sequence, they replaced both Will Smiths, either in part or whole. Junior was generated out of nothing, while in certain moments, a stunt performer’s face was swapped out for a version of Smith’s own, circa 2019 mug. They said that this freedom allowed Lee to direct the stunt performers to actually find the camera and show their faces, something that no stunt performer has ever heard in the history of stunt performance. But when the technology allows you to do some crazy stuff, some crazy stuff is what you will do.

The third and, in an odd way, most awe-inspiring scene, featured Junior talking to Clive Owen, who plays the movie’s big bad. He’s the one who initiated the cloning program and who has been raising Junior to be the cold-blooded killer he wants him to be. It’s a lengthy dialogue scene, full of the rich emotion Lee is most well known for. And you can see that emotion coming through on Junior’s face, as the tears well up in his eyes and then tumble down his cheeks. It’s both unreal and ultra-real at the same time. And the higher frame rate means that nothing is hidden between frames or glossed over in the editorial process. According to those visual effects supervisors, it’s something like 30% more pixels than you would normally use for a visual effects shot, because you can see so much of it. (Lee said that he recently approved a shot that the team had been working on for a solid year.)

Now, what does this all mean in terms of the future of cinema and the ways that technology can be used to enhance and extend the art of narrative filmmaking? I’m not really sure. The filmmakers seem to think they’ve stumbled upon something grand and profound. Legendary producer Jerry Bruckheimer, who has shepherded this movie through decades of development hell (that story is best saved for another time), described the film’s accomplishments as like “the leap from black-and-white to color.” Who knows what impact it will ultimately have, but for now, it’s safe to say that “Gemini Man” is one of the few must-watch movies of the fall, something that just has to be seen to be believed, the rare cinematic leap forward that has the potential to be an emotional breakthrough as much as it is a technological one.