'The Mule' Review: Clint Eastwood's Latest Movie Is Not One of His Best

A lot of aging actors try to persist with or recapture their youth, but Clint Eastwood isn’t one of them.

The actor-director’s “Unforgiven” reflected on and eulogized a bygone way of life, era and genre 26 years ago, and his films since then have increasingly embraced both his own advancing years and the sometimes questionable perspectives of a generation that is quite literally dying out. In “Gran Torino,” his most famous line of dialogue was “get off my lawn.” So it comes as little surprise that his first acting role in six years is playing a man bemusedly detached from modernity and oblivious to political correctness except where he believes it can help him personally.

“The Mule,” Eastwood’s fictionalization of the real-life travails of 90-year-old drug trafficker Leo Sharp, marginally gets by on leathery charisma. But the filmmaker’s reliable professionalism fails to transform one-dimensional characterizations and racial stereotypes into more than a showcase of the filmmaker’s own cultural blind spots.

Eastwood plays Earl Stone, a horticulturist who considers himself a workaholic but really just prefers the adulation of friends and colleagues to the hectoring if fully earned disapproval of Mary (Dianne Wiest), daughter Iris (Alison Eastwood), and granddaughter Ginny (Taissa Farmiga). Estranged from his family after pulling a no-show at Iris’ wedding, he accepts an invitation to attend Ginny’s nuptials 12 years later with the last remnants of his flower business piled in the back of his truck.

But after one of her guests offers him a chance to capitalize on his wanderlust, Earl soon finds himself shepherding increasingly big bags of cocaine across state lines.

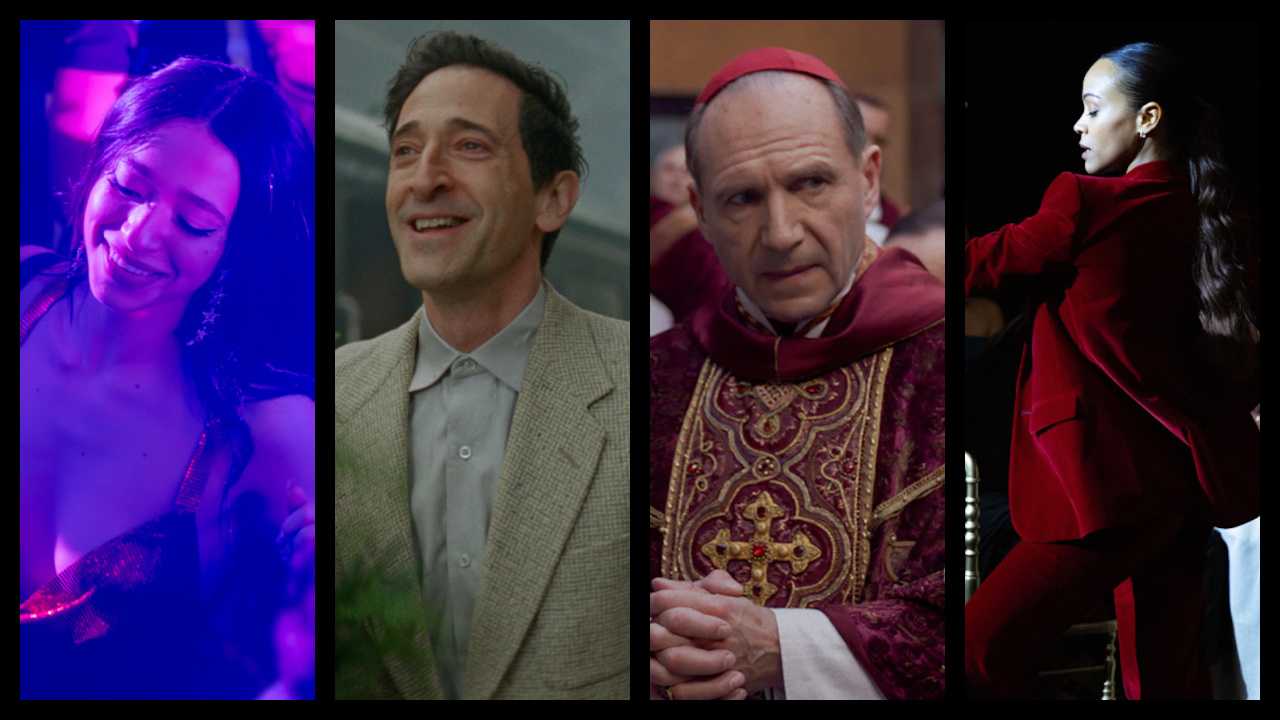

Though he’s unconventional, cranky, and unafraid of the gun-toting drug dealers like Julio (Ignacio Serricchio) -- who load his truck full of drugs -- Don Laton (Andy Garcia) takes a shine to Earl, who then quickly earns the drug lord’s confidence. But when young, intuitive DEA Agent Colin Bates (Bradley Cooper) and his partner, Trevino (Michael Pena), begin an investigation into Laton’s organization, their search reveals a trail of clues to an impossibly successful courier whose identity remains shrouded in mystery. This puts Earl in the crosshairs of the DEA, even as he uses his earnings to winnow his way back into his family’s good graces.

It’s hard to know where Eastwood is savvily trolling audiences with his portrayal of a cheerfully bigoted old man -- offering some kind of generational commentary -- and where he really just doesn’t care. But “The Mule” oozes with discomfiting racial stereotypes that are too often used for lazy punch lines. Casting Michael Pena and Lawrence Fishburne as DEA agents does not reconcile the fact that the drug dealers are all Mexican or Latino, nor does it alleviate Earl’s ongoing indifference to language that could be considered outdated or even offensive.

What these casting and narrative choices actually do is underscore Eastwood’s white privilege, both in character and real life. In much the same way Earl can slip past the authorities -- and even help his Mexican cohorts evade police attention -- Eastwood not only enjoys the latitude to play a role like this, but gets to do so with the benefit of the doubt that he’s not “really” racist, just a little old-fashioned. And worthy -- or even deserving -- of forgiveness.

Unfortunately, the movie doesn’t have much else to say about these subjects, at least not intentionally. Earl was a bad husband and parent, but his redemption comes frightfully easily once he starts plying friends and family members with stacks of cash for weddings, tuition and medical bills. Conversely, there is something theoretically interesting about a person like Julio, plucked from the streets and given a sense of purpose -- and power -- within Laton’s empire, but little more than lip service is paid to his situation, and only when Earl deigns to question it. Or in another scene when Bates and Trevino detain a Latino suspect, one who acknowledges that a routine traffic stop by cops qualifies as the most dangerous five minutes of his life. In this sequence, there’s little clarity as to whether Eastwood the storyteller is offering a real sense of sympathy or clowning people of color for self-victimization.

To be fair, none of Earl’s family members are rendered any better or more vividly than the dealers and intermediaries that he works with as a courier. Wiest delivers what may be the only deathbed reconciliation scene in history where the person who most badly needs to make amends is not the one in the bed. Farmiga’s Ginny alternately comes across as spoiled and petulant, though perhaps more as a byproduct of the director’s well-reported economy behind the camera than any particular choices either she or the script makes. But ultimately, it’s Eastwood’s show, and despite his iconic, grizzled charm, he seems to be working out some introspective curiosity that might be interesting to us if he let us in on his intent.

As it stands, however, “The Mule” feels like a conversation with an aging relative, one where you point out when they say or do something racist, they agree, and then they do it again anyway. You’re not going to change them, just like at 88, we’re not going to change Eastwood -- so it’s best to try and either accept what he has to offer or avoid him altogether.