Writer-Director Nicholas Meyer Looks Back on 'Time After Time' and Forward to 'Star Trek: Discovery'

Writer-director Nicholas Meyer's career is still going strong after more than 40 years in the business, and it's already proven to have a timeless quality.

Meyer first burst upon the entertainment scene with his bestselling 1974 novel "The Seven-Per-Cent Solution," featuring Arthur Conan Doyle's enduring fictional icon Sherlock Holmes encountering the real-life father of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud. Meyer sold the novel to Universal Studios on the condition that he be allowed to write the film's screenplay.

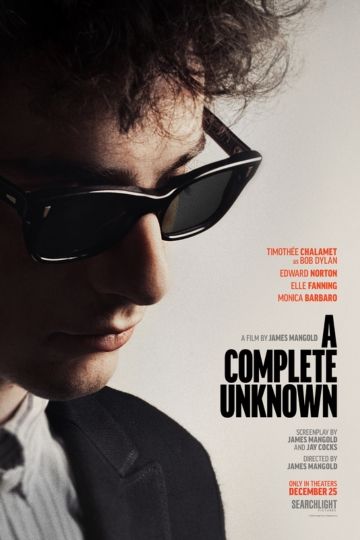

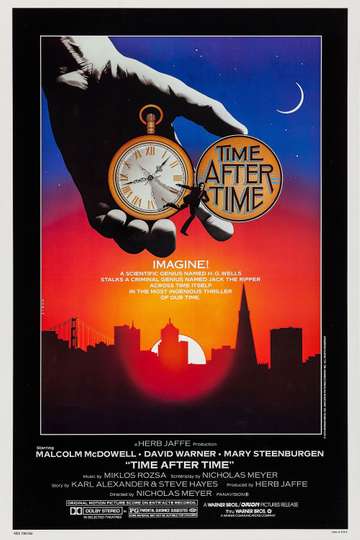

The film's subsequent critical and commercial success and his Academy Award nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay allowed him to make a similar bargain on his next film, "Time After Time": He'd adapt Karl Alexander's novel -- featuring real-life pioneering science-fiction author and futurist H.G. Wells (played against type by Malcolm McDowell) actually traveling through time to the present day in pursuit of legendary serial killer Jack the Ripper (David Warner) -- if he could direct it himself. "Time After Time" became one of the most popular films of 1979, later gathering a devoted cult following over the passage of decades that most recently resulted in a new Blu-ray release from Warner Archives.

In the interim, Meyer would become closely associated with another enduring staple of popular culture. He was the writer-director behind "Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan," widely considered the best of the "Star Trek" films; he co-wrote "Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home," the warmest, funniest, and most commercially successful of the franchise; and he wrote and directed the final big-screen adventure of the original Enterprise crew, "Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country."

And just to show that -- perhaps especially in Hollywood -- time has a way of coming around again, Meyer is returning to the Starfleet fold as a writer-producer on the forthcoming streaming series "Star Trek: Discovery" for CBS All Access, even as "Time After Time" is being adapted by Kevin Williamson ("Scream") into a weekly TV series for ABC; both series premiere in 2017.

Now considered not just a classicist but a maker of classics himself, Meyer joined Moviefone to gaze backward through the years at his debut film, and to look to the 23rd century horizon for his next project.

Moviefone: It was a pleasure to revisit "Time After Time," as I do frequently. When you think about this film -- your first directorial effort -- what is the feeling that bubbles up to the surface when you look back on it?

Nicholas Meyer: The first feeling is what enormous fun it was to make a movie, and how easy I thought it was -- you learn all the wrong lessons. I had such a wonderful time. I was surrounded by so many very, very able people keeping me from making worse mistakes than I did. I remember plunging into a real depression when the shooting was over because I was having such a great time.

The second thing that I remember, almost concurrently, is all the mistakes I made, all the things I did wrong, all the things I didn't understand and know how to do. I look at it -- it's obviously a very good movie; people have always loved it from the very beginning, but to me, it's a good movie despite all my mistakes. I can't help thinking it would have been an even better movie without them.

One of the things that strikes me is that there were certainly time-travel movies and television shows prior to this, but this movie really takes pleasure in the complications of time travel, things that are a little heady, and that we hadn't seen that often in these kinds of stories told on screen before you made it. Tell me about approaching that kind of challenge -- to make this story make sense to the uninitiated, as far as time travel goes.

I have to preface my remarks by saying that artists are not the best judges of their own work, any more arguably than people are of their own characters. The Scottish poet Robert Burns wrote, "I would that God the giftie gie us to see ourselves as others see us." It's tough. It's tough. So what I'm saying is sort of speculation that it should be treated as just another opinion. Because it is the filmmaker's doesn't make it definitive, and definitive is not a word in my opinion that belongs in any discussion of art.

Anyway, having said all that, it seems to me that the virtue of the movie is that, ultimately, it's less about time travel than it is about ... it's a sort of sociological investigation into societies of over 100 years ago, and now, and what has and what has not changed. In other words, it's the time travel movie that has meat on the bones.

Which is not to say that Wells's novel doesn't have them, because that novel supposes that in the distant future, the human race will have broken down into two subsets, the ineffectual and beautiful Elois, and the dangerous and primitive Morlocks. That may or may not happen. But "Time After Time" deals with more familiar contrasts. The contrasts between 1893 and 1979, and finds some mordant and distasteful irony in the fact that it's the Ripper who feels at home, and Wells, whose failed predictions of a utopia is lost. I think it's a movie with some mental meat on the bones.

Throughout your career, you've demonstrated an affinity for these iconic figures in the popular consciousness, whether they're fictional, like Sherlock Holmes or "Star Trek," or real-life but legendary and mythologized characters like H.G. Wells and Jack the Ripper. Why do you think you have a knack for getting to the meat of those figures, but also putting a fresh twist on them for the audience?

I really don't know, and again, taking what I say with a grain of salt as just one opinion, it seems to me that the difference between my novel, say "The Seven-Per-Cent Solution," and the movie "Time after Time," is that "The Seven-Per-Cent Solution" is a story of contrasting characters, individuals -- Freud and Holmes -- whereas the movie of "Time After Time" is really concerned, in a way, with archetypes: Wells standing in for civilization and a civilized, progressive, humane, forward-looking man. And The Ripper standing in for mindless, malevolent destruction.

They seem to me, at any rate, in "Time After Time," to be archetypes in that sense, more than they are individuals. This is just my opinion. As to why I have an affinity for this stuff, I wish I could tell you. I wish I could tell myself, but I don't know!

You've had to stand up for all of your casting choice for leading man, Malcolm McDowell. Tell me why that was important to you, at a time when Hollywood saw him primarily as a villainous type.

I think it's very interesting. I love actors, and I love acting, and I love watching them become different people. It is true that actors, not only in Hollywood but on the stage, are easily typecast. Eugene O'Neill's father was typecast all his life as the Count of Monte Cristo. He was Edmond Dantès. He couldn't escape it. But I think that is arguably wasting talent and wasting an actor, and it's sometimes fun to see an actor that you associate as one kind of character, jump into something completely different.

Having seen Malcolm McDowell as Alex the bad boy in "A Clockwork Orange," and then turning around and see him as Wells, this sort of civilized and gentlemanly guy, it's charming, it's a nice contrast. By the same token, we think of Alan Arkin as this comedic sort of person, but you look at him in "Wait Until Dark," and he could scare the sh*t out of you. He was one scary dude.

It's exciting to give him a chance, and to give us a chance to see those contrasts. It makes him a more interesting personality to watch while, arguably, it's certainly true that it's easier for Hollywood to shorthand these people. Same thing with Fantasy Island," and whatever, but we forget some of his other roles, and of course as Khan, as the supremely malevolent villain.

On the subject of "Star Trek," you're hard at work on your contribution to the upcoming series, "Discovery." What philosophical approach are you bringing to the material? I know that you became a student of "Star Trek" while you were working on the movies and refining your understanding of it. What did you take away from that time with the franchise that you're hoping to layer into what's happening now?

I don't know that it's very radical, but I would say that I'm a very Earth-bound person. So "Star Trek" has always worked best for me when it felt most real. So whether it's the stories or the costumes, and I'm just a cog in the wheel on this particular show -- it's not my show; I'm just working on it, but I'm trying to make things believable, and satisfy myself that they are genuine, as opposed to so fantastic that I kind of lose my bearings and don't know exactly where I am.

I think the best of science fiction always reflects what's going on with human beings. I keep trying to keep it, no pun intended, grounded.

You quickly connected the dots between "Star Trek" and C.S. Forrester's naval hero Horatio Hornblower and found the literary connection that helped you with the material -- something that you later discovered "Trek's" creator Gene Roddenberry also had in mind. Have you found something similar in your new work on "Star Trek," or are you continuing to mine the Hornblower aspect?

To me, the Hornblower aspect is ground zero for it. To me, once you use that as a template, everything else sort of, and I hate to say stems from, but fits in or grows from that conceit.

Having said that, there are other ramifications, I think. If you look at "Star Trek VI," that was very much inspired by the headlines of 1989, 1990, the wall coming down, and in particular the coup d'état that took place in the Soviet Union, which, by the way, the movie predicted. We shot it before it happened. When Gorbachev disappeared, we were already in the cutting room. We didn't know whether that poor man was alive or dead.

But that headline, as I said a little earlier, what happens during the course of life on Earth is a lot to do with what science fiction reflects, or recounts, or allegorizes, if that's a verb, but it's always about the human condition, no matter what planet they say they're on.

You directed a pretty landmark piece of television with "The Day After," and here we are in this bold new era of TV. What's got you excited about the possibilities for you in the new models of television that you're working in with "Star Trek"?

There is no question, as far as I can tell, that most Hollywood movies are not as interesting as the work that's being done on television. Now, my standard is not the eye candy standard. It's not about CGI, and motion capture creatures, and fantasy. A little of that goes a long way with me, and I get tired of it. It is much more interesting for me to watch people trying to figure out sh*t, and how to be alive, and solve human problems.

So I've done two Philip Roth movies. I did "The Day After." These are about what one would like to think of as grown-up stuff, and I guess what is generically described as, "Oh, drama -- you like drama." The answer is, "Yeah, I do." Whether it's drama, per se, or comedy for that matter. I can only look at the exploding car so many times, and all the escapism that Hollywood movies in particular seem so enthralled with. It seems like the worse trouble planet Earth gets into, the more we make these escapist, costume sci-fi things.

But in a way, I'm much more involved or engaged by movies like "Transparent," or "The Crown," or "Orange Is the New Black," or "Breaking Bad." For a writer, that's much more interesting.

Your movies have been loved for decades now, and you're still hard at work. Tell me about that experience, keeping it fresh and creatively exciting on your side of the equation.

I think you have to be very vigilant, so as not to either believe your own press or lose sight of your own standards, in a way, which is hard. It's very hard because you can start to coast on things that you know how to do, or think that you do well, or other people think you do well, and you have to fight for a certain level of objectivity, which is not always easy to attain, and I'm not sure that there's a royal road that leads to attaining it.

But you're always having to look over your shoulder and say, "Is this first class? Is this really something that you can be comfortable putting your name on?" Or are you just, as they say, "phoning it in," and plowing furrows that have already been plowed by either you or somebody else? I always say, when I'm teaching a class, I say to these young or younger filmmakers, I say, look, as artists, the only thing you have to offer is yourself. If you're just going to do it like the next guy, then move over and let the next guy do it, because it's going to be boring.

I have to be sure that what I'm trying to come up with is something that I really feel and that excites me. The French director Robert Bresson once said, "My job is not to find out what the public wants and give it to them. My job is to make the public want what I want." And the trick is to figure out: What do you want? What do you want? Not what you think other people will want. What do the fans want? To hell with that. The fans don't know what they want until they get it. If it was up to the fans, Spock wouldn't have died.

You've always shown such a fondness and respect for classic material. That's a word that's been now applied to your own work, and people quote lines that you wrote back to each other. What is that feeling like, at this stage in your career, to know that you're considered an author of classics, in a sense?

It feels really good. I like it. It feels great! It's nice. It feels like that the work has meaning, that it was in some way built to last. Who knows what the word "last" means. When Henry Kissinger went to China in 1973, and he got into a conversation, presumably with the help of an interpreter, with Zhou Enlai, and he said to Zhou Enlai, "What do you think of the French Revolution?" And Zhou said, "Too early to tell."

A lot of times I think that when we talk about things, and we're very lavish, we're quick, especially reviewers, to praise things. We say, "Oh, this is a masterpiece." I once remember getting into a conversation with my father who had introduced me to the play of "Cyrano de Bergerac," and I said, "Wow, this is a great play." He said, "Do you think so?" I said, "Yeah, definitely. Great." He said, "Well, let's talk in a hundred years, see if you still think so."

I just hope that in 100 years, if any of us are still here, or our descendants, or we haven't blown ourselves to smithereens, that somebody would be quoting a line or two of mine, even if they don't know it was written by me.

Let's close on the topic of genre. You've made two movies, with "Time After Time" and "Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home," that land routinely on people's all-time great time-travel films. What do you think is so appealing, eternally, to you and to the mass audience about the time travel story?

It's such an intriguing notion that it's the only kind of travel that hasn't happened, apparently. We've gone to the moon. We've gone to Mars. We haven't walked around it yet, but we've trolled around it. We go under water. We've found the Titanic. The only kind of travel we haven't done is maybe travel that's either much faster, or travel that takes us into another dimension. There's something intriguing about that possibility, I think.

Movies, for example, are such an inherently visual medium that the contrasts that two different eras presented with arguably the same characters wandering through totally different worlds. I know that Fox keeps trying to do another kind of travel movie. They want to do a remake of "Fantastic Voyage," which is another kind of travel -- travel inside the body -- and I'll certainly be eager to see that one.

We like being taken by movies to places that we normally can't go, whether it's Antarctica, or the place where "Game of Thrones" takes place [Westeros]. Movies can take us places. Taking us through time is maybe the ultimate place where they can take us.

Time After Time

Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home

Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan