Oscars 2016: Why the #OscarsSoWhite Boycott Only Scratches the Surface

Anyone who thinks the Oscars are trivial, that they're just about privileged people who live in a bubble giving each other golden trophies, wasn't paying attention this week.

The #OscarsSoWhite controversy has only grown more shrill and bitter in the week since the Academy announced its second straight slate of all-white acting nominees. Not only have numerous stars weighed in, but so have politicians, including presidential candidate Donald Trump and New York Mayor Bill de Blasio. So the discussion over the lack of diversity at the Oscars has affected the real world outside the Dolby Theatre -- as it should.

The underlying issue here is bigger than the Oscars, which only represent the end of the process. As many prominent movie folk have noted, from Spike Lee to Viola Davis to George Clooney, the problem is at the beginning of the process -- when the studios decide which stories to tell and whom to hire to tell them. Increase diversity there, and you'll increase it among the movies and individuals in the pool of eligible nominees.

Why does it even matter? Because black people, like everyone else, want to see people like themselves on screen and hear their own stories told. Because people of color also buy more movie tickets per capita than white people do, so you'd think Hollywood would try to do more to cater to its customer base. Because the success of black stars like Will Smith and Denzel Washington overseas -- where most of the box office comes from -- should have long ago put a stop to the industry belief that it's a waste of resources to make films about black people since foreign audiences won't pay to see them. And because Hollywood movies are not just one of America's most successful exports, but also represent the face (and faces) that America presents to the world, so why shouldn't the movies look more like America?

That's where the Academy comes in, since the Oscars are Hollywood's way of presenting its most positive image of itself. Just two years ago, when "12 Years a Slave" and Lupita Nyong'o won big, the message of the Oscars seemed to be: America's diversity is such a source of strength that it even allows us to take an uncompromising look at the ugliest part of our history. What's the message this year?

Right now, at least, it's one of strife and embarrassment. Jada Pinkett Smith was the first star to suggest a boycott, though she and husband Will are insisting that their non-attendance is about the larger shutout, not Will's own snub for "Concussion." Not sure if anyone believes that, especially after the dis from Will's former "Fresh Prince of Bel Air" co-star Janet Hubert. Whether or not the Smiths are sincere, the spat has made their boycott about ego and celebrity gossip, and less about the underlying issue.

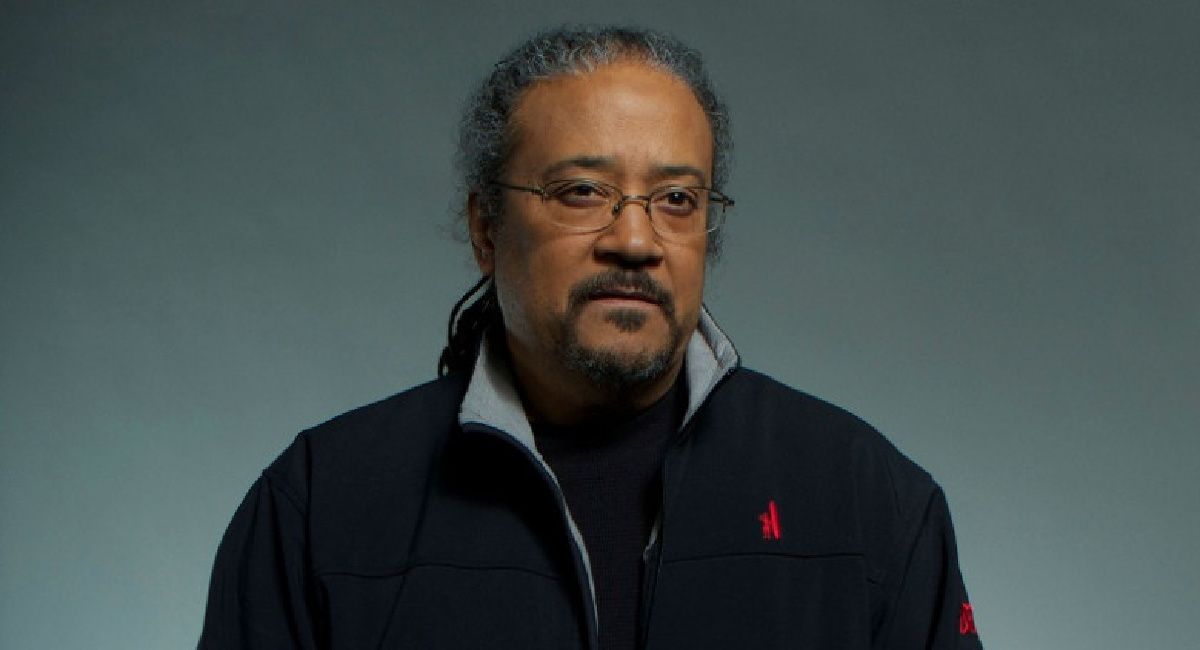

Ego may also have trumped good intentions in the case of music legend and former Oscar ceremony producer Quincy Jones. While dismissing the effectiveness of a boycott, he also threatened to walk, saying the Academy had asked him to be a presenter this year but that he'll only do it if he's allowed to address the diversity issue for five minutes. Let's hope he meant in private and not onstage; given how long the show runs every year, the Academy is unlikely to allow anyone to do anything for five straight minutes -- especially not give a political speech.

Special chutzpah points go to supporting Actor nominee Mark Ruffalo. First, he suggested that he was mulling the idea of joining the boycott; which performers of color should have been nominated in his place, this year and last, he didn't say. Then he tweeted that he actually would attend, in support of the sexual abuse victims whose stories he helped tell in "Spotlight." So he almost got to be the first actual nominee and the first white person to join the boycott, but he also gets to stay and not miss his potential winning moment, with a politically unassailable excuse. No doubt someone will scold him for playing one marginalized group against another, but for now -- well played, Ruffalo.

The outcry has been so loud that even Academy CEO Dawn Hudson and Academy President Cheryl Boone Isaacs have been forced to make diplomatically worded pronouncements expressing their disappointment over the homogeneity of the nominations and promising institutional changes while taking care not to disparage the achievements of the nominees.

No doubt the Academy overseers want to stem the talk of a boycott, and maybe they've succeeded. So far, the only people who've said they aren't coming are the Smiths, director and Academy documentary board member Michael Moore, and Spike Lee, who has said that, just because he's not coming doesn't mean he's urging anyone else to boycott.

Lee's behavior seems paradoxical, and not just because the filmmaker won an honorary Oscar last November for his groundbreaking body of work -- meaning that, had he shown up on February 28, there would actually be one black honoree recognized at the ceremony. But also because last year, when questioned about #OscarsSoWhite, he took the long view, citing how posterity had judged his Academy-snubbed 1989 movie "Do the Right Thing" (above) a classic while deeming that year's winner, "Driving Miss Daisy," a patronizing trifle. His argument last January was that true validation doesn't come from an award but from history. But after a second year of #OscarsSoWhite, he seems to have changed his mind.

In his announcement on Instagram that he would sit out this year's ceremony, Lee did acknowledge that change needs to happen in Hollywood boardrooms in order for it to happen at the Oscars.

So how, then, will an Oscar boycott help?

No one calling for a boycott has been able to explain that; nor has anyone who is calling for host Chris Rock to step down. Even Tyrese Gibson, who's the most prominent star urging Rock to join the boycott, has expressed reservations. He notes that Leonardo DiCaprio is his friend, and if "The Revenant" star finally wins his first Oscar, as he's widely expected to do, the award will seem tainted by the controversy.

Tyrese's misgivings introduce a rich irony: the sense that any white winner this year will have to wonder whether he or she won based on racial preference, not just merit. That, after all, is the mirror version of the argument many have been making, that the protest is unjustified because maybe there just weren't enough worthy black performances, this year or last. That argument assumes that all the white nominees did get in on merit alone, that there's no reverse affirmative action at work.

Maybe they did, but it's unlikely because the Oscars have never been entirely about merit. There are always other considerations, including Hollywood politics, money, and the simple fact that there are always more worthy candidates than nomination slots. (That's why the awards are so hard to handicap.)

But the argument that snubbed black actors shouldn't complain because white actors get snubbed too doesn't hold water. The late Alan Rickman was widely acknowledged to be one of the finest actors in the English language, yet he never got one Academy Award nomination. Who can say why? But at least the reason wasn't that the Academy didn't have enough white male members to make sure he wasn't overlooked, and it wasn't that Hollywood wasn't making enough movies with white male characters for him to enjoy a proper showcase for his talents.

Under Boone Isaacs, the Academy has been working to diversify its membership for the past four years. And on Thursday came the news that the Academy may institute some rule changes, perhaps as soon as next week, that could eventually create a more inclusive slate, such as fixing the number of Best Picture nominees at 10 (instead of a variable number between five and 10) and increasing the number of nominees in the acting categories.

Of course, there will be complaints at first that this is just watering down the awards by making them less exclusive. But again, the Oscars have never been solely about excellence anyway, and similar complaints made back in 2009 when the Academy first expanded Best Picture beyond five nominees have long since been ignored and forgotten by all.

The real problem with the proposed rule changes is that they address only the symptom, not the cause. That's something that Hollywood will have to address far away from the red carpet, and not just during the one time each year when the whole world is paying attention.